New Regulations Permit Use of Value-Based Insurance Design in State Medicaid Programs

Originally Produced: July 2013 Updated: June 2016.

Introduction

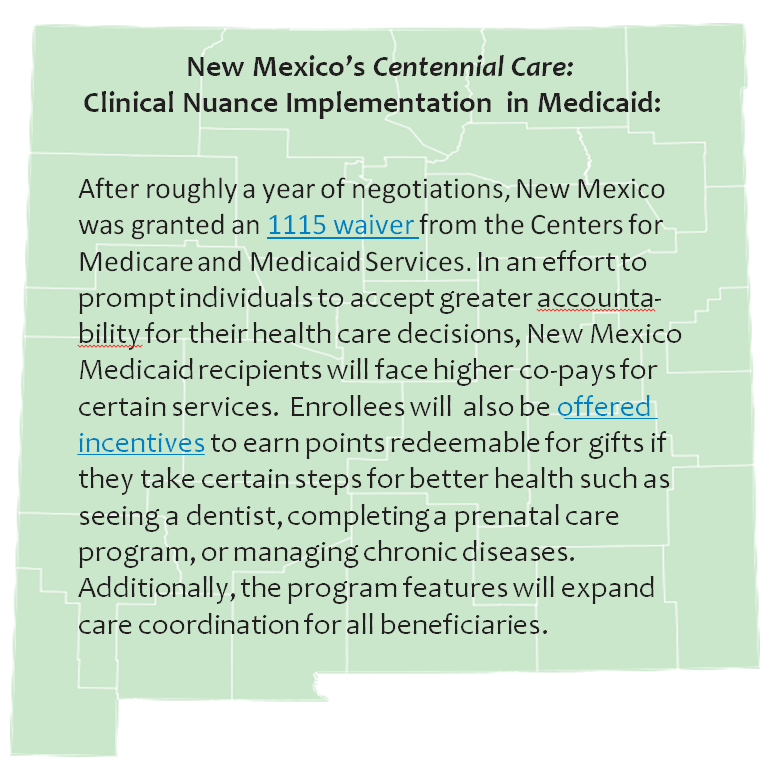

Value-Based Insurance Design (V-BID) is an innovative approach that can improve clinical outcomes and contain costs. The basic premise of V-BID is to align consumer incentives with value by reducing barriers to high-value health services and providers (“carrots”) and discouraging the use of low-value health services and providers (“sticks”). When “carrots” and “sticks” are used in a clinically nuanced manner, V-BID improves health care quality and controls spending growth. The concept of clinical nuance recognizes that: 1) medical services differ in the benefit provided; and 2) the clinical benefit derived from a specific service depends on the patient using it, as well as when and where the service is provided. Incorporating greater clinical nuance into benefit design, payers, purchasers, taxpayers, and consumers can attain more health for every dollar spent.

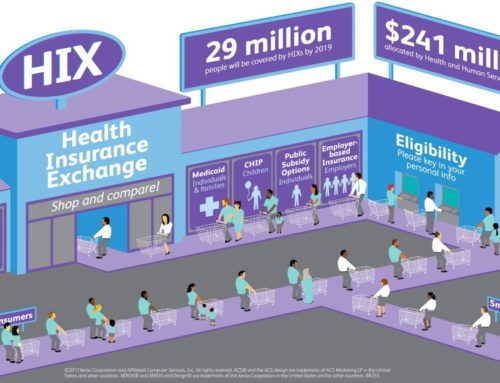

State Medicaid programs cover some of the nation’s most vulnerable citizens and account for a large and growing portion of state budgets. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently finalized rules (CMS-2334-F) giving state Medicaid programs greater flexibility to vary enrollee cost-sharing for drugs as well as certain outpatient, emergency department, and inpatient visits. If implemented successfully, a clinically nuanced cost-sharing model can enhance the use of high-value clinical services and reduce utilization of unnecessary and costly services, while fostering consumer engagement and personal accountability. If V-BID principles are used to set enrollee cost-sharing levels, Medicaid programs can improve quality of care, remove waste, and mitigate the legitimate concern that non-nuanced cost-sharing may lead individuals to forgo clinically important care.

Cost-Sharing for Outpatient and Inpatient Services

Outpatient services have inherently different clinical values. Under the final rule, Medicaid programs are free to impose cost-sharing (within certain income-based boundaries) on select outpatient services while allowing other services to be provided without cost-sharing. For example, states may choose to impose the maximum allowable cost-sharing for use of low-value services—such as those identified in the Choosing Wisely initiative or the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF) Grade D recommendations.

The value of a particular clinical service may depend on the specific provider or the locus of care delivery. Under the new rule, states may vary cost-sharing for a particular outpatient service in accordance with who provides the service and/or where the service is delivered. This flexibility might be useful as states identify certain high-performing health care providers or care settings that consistently deliver superior quality. For example, a state might wish to impose a co-payment for clinician office visits, but eliminate cost-sharing for those office visits that take place at a recognized Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH).

The final rule also allows state Medicaid agencies to target enrollee cost-sharing (within certain income-based boundaries) to specific groups of individuals based on clinical information (e.g., diagnosis, clinical risk factors). In doing so, CMS has recognized that there are compelling reasons for Medicaid programs to impose different levels of cost-sharing on different groups of enrollees for certain medical services. This flexibility is a crucial element for the safe and efficient allocation of states’ Medicaid expenditures. Under such a scenario, a state may choose to exempt certain enrollees from cost-sharing for a specific service on the basis of a specific clinical indicator, while imposing costsharing on other enrollees for which the same service is not clinically indicated. For example, annual retinal eye examinations are recommended in evidence-based guidelines for enrollees with diabetes mellitus, but not recommended for those without the diagnosis.

Targeting specific populations is key to clinical nuance. Improved access to evidence-based services for individuals at risk for and diagnosed with chronic conditions – who are often at greater risk for avoidable and expensive acute-care utilization – has the potential to slow disease progression and reduce costly complications. Reducing cost-sharing for these services for all enrollees, regardless of clinical indication, can lead to overuse of services, wasted dollars, and the potential for harm.

Cost-Sharing for Drugs

Given the considerable evidence examining the impact of enrollee cost-sharing on prescription drug adherence, it is essential that states differentiate enrollee cost-sharing for prescription drugs based on the drug’s clinical value. The rule provides states with the flexibility for differential cost-sharing on preferred ($0-$4) and non-preferred drugs (up to an $8 copay). The final rule retains the states’ ability to differentiate preferred and non-preferred drugs within their programs through Preferred Drug Lists. This flexibility will allow states to develop innovative cost-sharing structures that will encourage the use of high-value therapies and discourage harmful and low-value treatments. Under this model, preferred and non-preferred categories are determined based on their clinical value, not solely on their acquisition cost.

There are approximately 9 million people who are considered to be Medicare-Medicaid dually eligible, and thus receive their prescription drug coverage through the Medicare Prescription Drug Program. CMS should examine how the use of clinical nuance in enrollee cost-sharing may be extended to these Medicare Part D plans as well as Medicare Advantage plans.

One example of the implementation of V-BID principles in enrollee cost-sharing is the new 2021 Medicare Part D Senior Savings Model. Beginning on January 1st, 2021, CMS will allow Medicare Part D and Medicare Advantage sponsors nationwide to offer a benefit design that includes predictable co-pays for insulin. Beneficiaries who opt-in to this voluntary model will be able to receive a thirty-day supply of a broad set of plan-formulary insulins for no more than $35. Participating beneficiaries are expected to save an average of $446 per year in out-of-pocket costs relative to average cost-sharing amounts in 2020. This V-BID implementation has the potential to help millions of diabetic, dual Medicaid-Medicare enrollees access insulin and manage their diabetes through reducing and stabilizing monthly costs.

Non-Emergency Use of the Emergency Department

The new rule gives Medicaid plans the option to impose up to an $8 copayment for non-emergency services provided in the emergency department (ED). Unlike other services such as clinician visits and prescription drugs, the evidence-based application of “clinical nuance” is less clear in the emergency room setting. CMS, in partnership with the states, should ensure that increases in ED cost-sharing can be accurately applied only in truly non-emergent cases so that increased co-payments for ED visits do not lead Medicaid enrollees to delay or forgo necessary care.

Conclusion

Incentive-based V-BID programs (“carrots”) can improve quality of care and reduce undesirable acute care utilization, such as emergency room visits and hospitalizations. When targeted correctly, these incentive-only programs can be cost-neutral over the medium term. V-BID approaches can also incorporate cost-sharing increases (“sticks”) to also incorporate cost-sharing increases (“sticks”) to enhance personal accountability, discourage patients’ use of targeted low-value services, and address concerns that indiscriminate “across-the-board” increases in patient cost-sharing reduce the utilization of high-value services. V-BID programs that include both carrots and sticks may be particularly desirable for states facing budget challenges.

The ultimate test of health reform will be whether it provides coverage that promotes access to care, improves health, and addresses rapidly rising costs. Instead of focusing exclusively on aggregate spending, or how much is spent, attention should be turned to how well we spend our health care dollars. As such, clinically-nuanced, value-driven strategies that encourage the use of clinically-effective care and discourage the use of low-value services can help contain costs and improve enrollee health outcomes.