The “Cadillac” Redesign: A Role for Clinical Nuance & V-BID

Originally Produced: October 2013 Updated: September 2019

Introduction

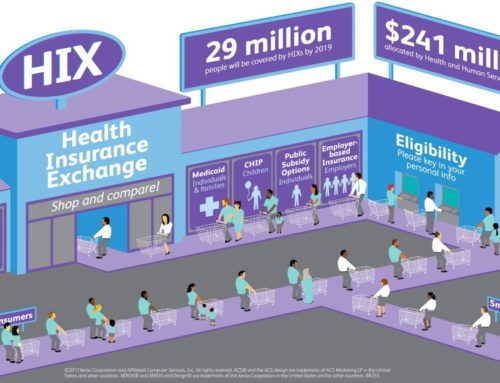

The High-Cost Plan Tax, or “Cadillac Tax” was established in Section 49801 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)1. Originally slated to be implemented in 2018, the tax has been twice delayed by Congressional action, most recently in January of 2018. Now scheduled to take effect in 2022, the excise tax will be levied on certain generous health plans. Specifically, if a plan’s benefits exceed a designated cap, the insurer or plan sponsor must pay a 40 percent excise tax on each dollar above the cap. These thresholds are estimated to be $11,200 for individual coverage and $30,100 for family coverage.2 This policy remains controversial and in flux; in July of 2019, the US House of Representative voted overwhelmingly (419-6) to repeal the tax. A companion bill has been introduced in the Senate, and is expected to be voted on in late 2019 .3

Certain insurance products, often referred to as “Cadillac” plans, have high premiums and offer a rich menu of benefits with limited deductibles and cost-sharing. Cadillac plans are popular among enrollees who appreciate broad provider networks and an expansive list of generously covered services, regardless of clinical evidence, quality, or cost. Due to the limited cost-sharing at the point of service, these plans do little to engage consumers in making cost-conscious choices, and are susceptible to inappropriate utilization — thereby exposing consumers to unnecessary health risks and payers to wasteful expenditures. Further, because health insurance benefits are tax-exempt, employers have had little incentive to stem generous benefits. Combined, these adverse incentives impose a costly burden on our health delivery system.

To respond to these inefficiencies, the “Cadillac tax” on high-cost health plans was intended as an attempt to hold payers more accountable for the benefits provided, lessen the tax-free inducement for employers to offer increasingly generous plans, and diminish the resulting incentive for enrollees to use health care services with practically no restrictions. An additional impetus for the tax was to raise revenue to finance PPACA’s expansion of insurance coverage. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the excise tax will raise $3 billion dollars during its first year and increase to $20 billion dollars after six years.4

Due to these cost estimates, employers and plan sponsors are justifiably concerned. In the years following the tax, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) will update the threshold cap by the consumer price index (CPI) plus one percent, and in each successive year by the CPI. Most recent analyses in 2018 indicate that 1 out of 5 employers will be affected by the Cadillac tax.2 Since the update to the threshold cap grows more slowly than health insurance premiums, the Cadillac tax will affect an increasing number of plans as years pass. As a result, some estimates suggest that employers with plans reaching the threshold will reach 28% in 2025 and 37% in 2030 (excluding FSA contributions), and 38% in 2025 and 46% in 2030 when FSA contributions are taken into account.2 While it is unsure whether the tax will be implemented in 2022 or be further delayed, plan sponsors are already responding to the potential future tax by altering their health benefits. In fact, 7 percent of small firms and 26 percent of large firms said they had altered their benefit designs for 2018 to mitigate the potential impact of the Cadillac Tax. In all likelihood, efforts to revise plan offerings to avoid the penalty will increase as the implementation of the Cadillac tax draws near.

Clinical Nuance and V-BID: Redefining “Luxury”

As payers maneuver to avoid the Cadillac tax, they should aim to maximize population health through the efficient reallocation of medical spending. Rather than unpopular indiscriminate benefit reductions or “one-size-fits-all” cost-sharing increases frequently used to control utilization and lower costs, the basic tenets of “clinical nuance” must be considered as insurance benefits are redesigned. These tenets recognize that: 1) medical services and providers differ in the benefit provided; and 2) the clinical benefit derived from a specific service depends on the consumer using it, who provides it, and where it is delivered.

To encourage consumers to take better advantage of high-value services and actively participate in decision-making about treatments that are subject to misuse, private- and public-sector payers began to implement a concept known as Value-Based Insurance Design (V-BID) more than a decade ago. The basic V-BID premise calls for a clinically nuanced benefit structure that reduces consumer cost-sharing for beneficial services and high-performing providers. In an analysis of health care reform proposals from seven national policy centers and stake-holder coalitions, V-BID was unanimously included. Compared to plans without such clinically nuanced cost-sharing, incentive only (“carrot”) V-BID programs that lower cost-sharing for targeted services have consistently demonstrated improved adherence with no net increases in aggregate expenditures. More recently, V-BID programs have incorporated nuanced disincentives (“sticks”) to discourage use of low-value care. Key stakeholders – such as the large and growing number of medical professional societies participating in the Choosing Wisely initiative – agree that discouraging the misuse or overuse of identified low-value services must be part of the spending reallocation strategy.

In a Cadillac plan redesign, cost-sharing is applied only to those low-value services whose use would be questioned from a clinical evidence perspective. Thus, by reducing the use of low-value care, the new plan is just as luxurious as a Cadillac in terms of its rich coverage for evidence-based services (e.g., seat belts and anti-lock breaks), but it no longer includes unlimited access to services of unproven clinical value (e.g., power trunk or heated leather seats). One example of such a plan is, VBID-X, a benefit design template that reduces spending on low-value services through higher cost-sharing, thereby creating room for more generous coverage for specific high-value care, without the need to increase premiums or deductibles.

It is important to note that the V-BID program does not determine what is covered and what is not. Instead, V-BID alters the amount of consumer cost-sharing based on the health benefit provided by a specific clinical service – not the price of that service. Enrollees continue to have access to services of questionable value, but are responsible for paying a higher portion of the costs.

Conclusion

The ultimate test of health reform will be whether it provides coverage that promotes access to care, improves health, and addresses rapidly rising costs. Instead of focusing exclusively on how much is spent, attention should be turned to how well we spend our health care dollars. By using clinical nuance to intelligently redesign a health plan that better engages consumers in making cost-conscious health decisions, plan sponsors may avoid the excise tax while still providing “Cadillac-quality” benefits. As such, value-driven strategies that encourage the use of clinically-effective care and discourage the use of low-value services can help contain costs, improve enrollee health outcomes, and permit payers, purchasers, taxpayers, and consumers to attain more health for each dollar spent.

References

- https://www.irs.gov/affordable-care-act/affordable-care-act-tax-provisions

- https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/how-many-employers-could-be-affected-by-the-high-cost-plan-tax/?utm_campaign=KFF-2019-Health-Costs&utm_medium=email&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-_NIPAJeql-Axa_d4PU2GmDMO1c3Uvcm3FWhNO9Vct8KS0dx3QeEGJExzeB80HY66q4FQJV8SMPAJhqK2_rFqrzWA-huQ&_hsmi=74562169&utm_content=74562169&utm_source=hs_email&hsCtaTracking=2373f60a-db59-406b-953f-1fa0dc660555%7C066191af-1dd9-4604-9e27-78f4d209831c

- https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748

- https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/2016/52246