Precision Patient Assistance Programs to Enhance Access to Clinically Indicated Therapies: Right Drug, Right Time, Right Cost-Share

Precision Patient Assistance Programs to Enhance Access to Clinically Indicated Therapies: Right Drug, Right Time, Right Cost-Share

Cost-Sharing and its Consequences

Consumer cost-sharing for medical care and medications is high and getting higher. The average deductible for employer-sponsored single coverage increased by more than 250% between 2006 and 2016, and is now nearly $1,500.1 Even after any applicable deductible has been satisfied, patients are often liable for high copayments and coinsurance. The average copay or coinsurance for a fourth-tier drug in employer-sponsored coverage was $102 in 2016. In 2016, more than 25% of Medicare beneficiaries spent 20% or more of their income on out-of-pocket health care costs,2 with a significant share of this spending devoted to coinsurance of 25-33% for specialty medications. Most Medicare Part D beneficiaries taking a single specialty drug will pay no less than $2,000 over the course of one year[a].3 For Medicare Part D beneficiaries using common treatments for rheumatoid arthritis, Hepatitis C, and multiple myeloma, out-of-pocket cost-sharing frequently surpasses $4,500, $6,500, and $11,500 respectively.3

Cost-sharing at these levels is associated with many deleterious consequences. Patients subject to greater cost-sharing tend to reduce use of services and medications – and the greater the cost-share, the greater the corresponding reduction in service use.4–6 In response to across-the-board increases in cost-sharing, many studies find that patients reduce use of both high- and low-value care in similar proportions.4,7 Increased acute care utilization and poorer health outcomes may result.5,6,8,9 Research suggests that cost-related underuse of evidence-based services disproportionally impacts poorer Americans and those with chronic conditions.8–11

Cost-sharing is a useful tool for payers and purchasers to encourage prudent use of health care dollars. Historically, however, cost-sharing has been “one-size-fits-all,” and has failed to distinguish between high- and low-value clinical services and therapies.

Value-Based Insurance Design

Value-based insurance design (V-BID) entails better aligning of out-of-pocket cost-sharing with the value of the underlying service – i.e., lowering cost-sharing for high-value services and/or increasing cost-sharing for low-value services. Such an approach encourages the use of high-value care while maintaining or strengthening incentives to avoid wasteful spending.12 V-BID incorporates clinical nuance, “recognizing that the clinical benefit of a specific service or therapy depends on who receives it, who provides it, and where and when in the course of disease the service or therapy is provided.”13 These clinically nuanced benefit designs have repeatedly been shown to reduce cost-related non-adherence for many types of conditions.14

Most payers and purchasers that have implemented V-BID have limited their efforts to relatively small populations and a small subset of high-value services and medications.14 Ideally, benefit designs would reflect V-BID principles for all services and medications, through tools such as dynamic cost-sharing.15 At present, however, V-BID is not common for high-cost medications, and patients are frequently exposed to high costs for clinically-indicated medications. Patient assistance programs frequently serve to fill the void, reducing the risk of “financial toxicity” and cost-related nonadherence.

Patient Assistance Programs

Patient assistance may be delivered in several forms, including copayment assistance cards (commonly referred to as “copay cards,” “discount cards,” or “savings cards”), manufacturer assistance programs, and grants from charitable patient assistance foundations.

Patient Assistance Infographic

Copayment Assistance

Copayment assistance is generally targeted to individuals with commercial coverage; these programs cannot be used by individuals enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, or other federal health care programs.16,17 Offers are typically advertised and delivered to patients, prescribers, and pharmacists through consumer-facing magazines, provider-facing journals, pharmaceutical company representatives, and websites. Pharmacies process the discount card after processing the patient’s primary insurance. Depending on the patient’s standard cost-sharing liability and the terms of the card itself, the patient may be left with a small or nominal copayment (e.g., $10 after application of the Enbrel Support Card,18 $5 after application of the Harvoni Co-pay Coupon,19 or $4 after application of the Lipitor Savings Card20). Discount cards usually have a maximum value per fill, so patients who have not yet satisfied a deductible applicable to the pharmacy benefit may still be subject to very high cost-sharing. Cards may also have an annual cap on support offered per patient per year.

As of May 2016, there were more than 700 discount cards available – a drastic increase from less than 100 in 2009.21 According to IMS Health, about 10% of prescriptions were paid for, in part, with a copay card – an increase of 7 percentage points since 2010.21 The voluminous claims-based literature on medication adherence and initiation is rarely able to identify the use of copay cards from the available administrative data. There are several noteworthy exceptions:

- A 2014 study by Starner et al. used claims records and administrative data on prescriptions for specialty medications from a specialty pharmacy to find that 77% percent of potential patient cost-sharing ($12.9 million) was offset by drug coupons. Before discount cards, 57% of prescriptions had a cost-share of greater than $50; this percentage decreased to 3% after discount cards were applied. The researchers also studied abandonment – that is, failure to pick-up a prescription that was ordered – by examining claims for multiple sclerosis and biologic anti-inflammatory specialty drugs that were adjudicated but later reversed. The study found that as actual out-of-pocket costs (i.e., cost-sharing net of any discount cards) increased, so too did abandonment. Patients abandoned more than half of all prescriptions requiring $2,000 or more in actual out-of-pocket costs.22

- A 2015 study by Lee et al. studied administrative data from a large specialty pharmacy for claims from patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma. Use of financial assistance (copay card or other assistance, see below), as facilitated by the specialty pharmacy, reduced patient out-of-pocket costs by an average of $147 per prescription ($359 in reduced out-of-pocket expense for the first prescription).23

- A 2016 study by Daubresse et al. used a database of pharmacy transactions to examine associations between use of discount cards for branded statins and medication utilization. The researchers found that patients using copay coupons had higher levels of persistence; coupon users were significantly less likely to terminate statin therapy (any type) over a four year period than patients who did not use copay cards (50.6% versus 61.1%).24

- A 2017 study by Zullig et al. examined the role of patient assistance for anticancer medications provided through the specialty pharmacy of an academic cancer center. The authors found that patient assistance was applied to 12% of the prescription fills examined. Among this 12% of prescriptions, patient out-of-pocket liability was reduced by a median of $411 per prescription; out-of-pocket liability was reduced by at least $520 in more than a quarter of instances.25

Other Manufacturer-Sponsored Patient Assistance Programs

In addition to copay assistance, manufacturers sponsor a variety of additional efforts that enable access to medications. Qualifying patients may receive free or low-cost medications by mail to their home or provider’s office, access to a nurse by telephone, assistance navigating insurance requirements, and other types of support.26–29 Discounted drugs are typically only available to individuals earning less than a specified amount, which may vary widely across programs (one study reported that eligibility cut-offs ranged from about $51,000 to $125,000 in annual income).26 Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries may be eligible to receive free or reduced cost medications, provided they do not submit claims for reimbursement to their carrier. Applications are generally required for participation. Information on whether the medication is the best clinical option is generally not ascertained, and the patient must typically coordinate with any other sources of coverage on his or her own.

Charity-Sponsored Patient Assistance Programs

Independent charitable foundations and some patient advocacy organizations administer patient assistance programs as well. Such organizations include, but are not limited to, The Assistance Fund, Good Days, the HealthWell Foundation, Needymeds, Patient Services Inc., the Patient Advocate Foundation, and the Patient Access Network Foundation. Most of these organizations administer disease-specific funds, and patients generally must meet eligibility criteria related to family income. These programs collectively provide hundreds of millions of dollars in cost-sharing assistance annually, and generally serve as programs of last resort. Funds are typically disbursed as grants to reimburse individuals for out-of-pocket expenses associated with copays, deductibles and co-insurance incurred in filling their prescriptions, and/or by paying claims to providers.

Unlike programs administered by manufacturers, charity-administered programs may provide grants to patients receiving drugs reimbursed through Medicare or Medicaid.16,17 Patient assistance programs serving Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries must be carefully designed to avoid running afoul of the federal anti-kickback statute and the beneficiary inducements civil monetary penalty, and most operate within the parameters of guidance set forth in charity-specific OIG Advisory Opinions. Conditions of permissible programs include:

- Ensuring that grantmaking is not contingent on the use of certain physicians, certain pharmacies, or certain drugs;

- Maintaining independence from pharmaceutical manufacturers in governance and decision-making; and

- Applying standards for eligibility assistance in a manner that is consistent and based on financial need.16,17

According to formal guidance from the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, patient assistance charities are permitted to focus grantmaking on certain conditions, but cannot:

define their disease categories so narrowly that the earmarking effectively results in the subsidization of one (or a very few) of donor’s particular products. For example, we [OIG] would be concerned if disease categories were defined by reference to specific symptoms, severity of symptoms, or the method of administration of drugs, rather than by diagnoses or broadly recognized illnesses or diseases.16 (emphasis added)

Recent OIG advisory opinions have emphasized that charities must define conditions broadly. Neither the “stages of a particular disease” nor any other method of “narrowing the definition of widely recognized disease states” is permissible.30

Charity-administered programs have several limitations. First, programs frequently exhaust available funds before the needs of all potentially eligible patients are met within any particular disease. As a result, disease-specific funds may open and close several times during a 12-month period, based on the availability of donations. Second, patients with limited disposable income may incur hardship in waiting for reimbursement after paying high out-of-pocket costs and coordinating the submission of needed documentation to the assistance program. Third, given the constraints of the OIG guidance, charity resources generally cannot be prioritized based on adherence with evidence-based guidelines and clinical necessity. Patients must typically have access to support for all FDA-approved therapies for a given condition. In effect, federal requirements may deter charities from offering clinically nuanced patient assistance programs.

Problems with Status Quo

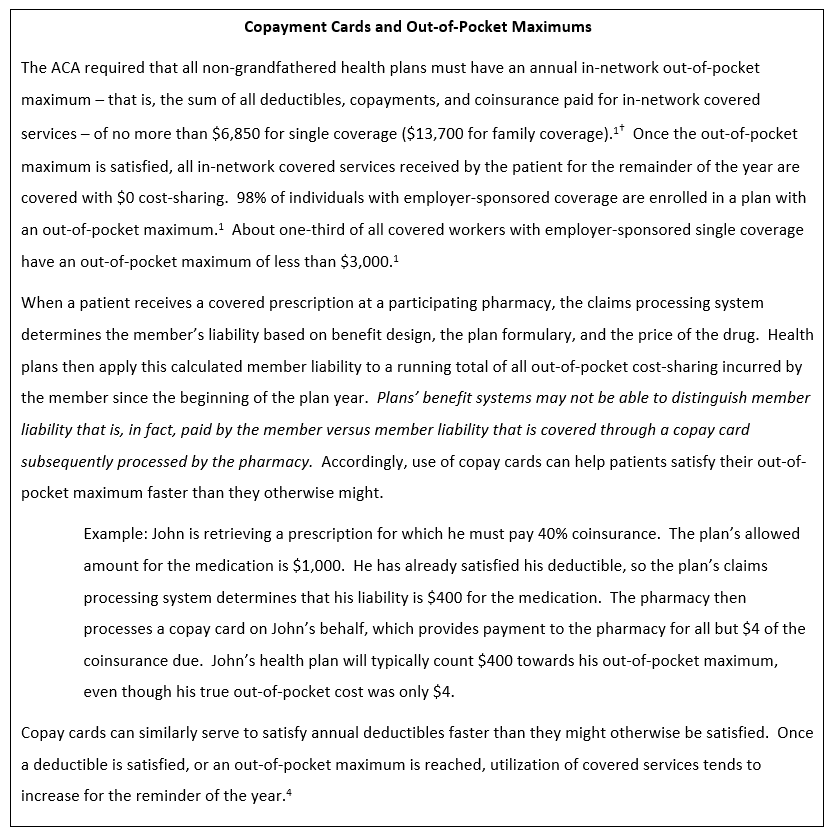

Patient assistance programs serve to address increasingly salient concerns around cost-related access to clinically indicated prescription medications. However, some payers, purchasers, and researchers have expressed concerns that copay cards in particular undermine reasonable incentives for clinicians and patients to respect plan formularies and speed members toward deductibles and out-of-pocket maximum amounts they might not otherwise satisfy, thereby increasing expenditures (see text box).31–38 Use of copayment cards for branded medications when generic equivalents are available has drawn particularly harsh attention.32,33

Commercial payers generally maintain the prerogative of denying all coverage for any given drug (i.e., excluding it from the formulary), and some pharmacy benefit managers have used these techniques for select drugs with copay cards available.36,39 Plans and pharmacy benefit managers can also increase use of step therapy and prior authorization in response to the availability of copay cards,31 and they may manually subtract assistance amounts from the deductible and out-of-pocket maximum accumulators. This may be particularly problematic for copay cards limiting assistance to an annual maximum amount.

If a plan reverses accumulation in these cases, the patient may be at risk  of experiencing “sticker shock” midway through the year once the copay card’s maximum assistance amount has been reached – potentially increasing the risk of prescription abandonment and adverse health outcomes.

of experiencing “sticker shock” midway through the year once the copay card’s maximum assistance amount has been reached – potentially increasing the risk of prescription abandonment and adverse health outcomes.

Copay card programs might counter accumulator reversal strategies by operating assistance programs that are not visible to the payer. These “competing” strategies can create a great deal of confusion and administrative burden for physicians and patients who would clinically benefit from therapies that are not easily accessible.

A Better Way Forward through Alignment

Cooperative strategies among payers and manufacturers that aim to serve patients’ best interests are preferred over the at-times adversarial relationships that currently exist. Collaborative approaches based on the specific clinical needs of a patient can potentially enhance patient-centered outcomes, while reducing the harm associated with high cost-sharing and finite patient assistance resources.

Clinically Nuanced Copayment Assistance

Recognizing that “one-size-fits-all” cost-sharing for high-cost medications is likely to persist, plans, pharmacy benefit managers, and manufacturers could minimize potential harm through new partnerships that facilitate the use of patient assistance when high-cost medications are used in high-value clinical scenarios. A “truce” might include the following provisions, each of which could serve to enhance access to clinically indicated therapies and decrease the financial and logistical burden on patients/families and their clinicians:

- Payers would accept the use of support for consumer cost-sharing when a particular medication is clinically indicated and has low potential for inappropriate use. This would mean supporting patient access to high-value medications when clinically appropriate and forgoing utilization management (e.g., step therapy, prior authorization, formulary exclusions, etc.) in these situations. Efforts to exclude copay assistance from out-of-pocket maximum and deductible accumulators might be limited to circumstances wherein the medication was not the clinically indicated option (e.g., use of a branded drug when a generic alternative was available). This might reduce the risk of decreased medication adherence resulting from unexpected cost-sharing a member may face if/when a card reaches an annual or monthly limit. Payers might also encourage their contracted providers and care managers to connect patients to patient assistance resources when clinically appropriate.

- Manufacturers would ensure information on clinical appropriateness – including scenarios where a medication is not clinically appropriate – is well-communicated in patient assistance materials. For manufacturer-administered programs serving those with commercial coverage who are underinsured, applications might inquire as to whether first-line treatments had been appropriately tried.

Such arrangements would benefit from consensus on clinically indicated uses of medication. Designation of high-value could be based upon alignment with clinical guidelines issued by professional societies, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network pathways, or other trusted, third-party sources. In many instances, this designation of high-value could include use of recommended first-line therapy prior to more expensive biologic or specialty medications (e.g., use of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis prior to use of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-inhibitor or janus kinase (Jak) inhibitor).40 In other instances, it might include the presence of certain patient-specific characteristics (e.g., biomarkers) that make a targeted therapy appropriate (e.g., use of trastuzumab (Herceptin) for patients with early-stage breast cancer that is human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+)).41

Such arrangements would benefit from consensus on clinically indicated uses of medication. Designation of high-value could be based upon alignment with clinical guidelines issued by professional societies, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network pathways, or other trusted, third-party sources. In many instances, this designation of high-value could include use of recommended first-line therapy prior to more expensive biologic or specialty medications (e.g., use of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis prior to use of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-inhibitor or janus kinase (Jak) inhibitor).40 In other instances, it might include the presence of certain patient-specific characteristics (e.g., biomarkers) that make a targeted therapy appropriate (e.g., use of trastuzumab (Herceptin) for patients with early-stage breast cancer that is human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+)).41

Ultimately, payers and manufacturers alike have critical roles to play in enabling more seamless access to the right medication at the right time to improve the experiences of patients, families, and providers. Payers and purchasers might also benefit from some savings due to reductions in hospitalizations and emergency room visits that result from greater adherence.

Enabling Clinical Nuance in Charitable Patient Assistance

In Part D, OIG could update its guidance to enable clinically nuanced patient assistance programs, while maintaining the “firewall” between manufacturer donations and patient-facing grantmaking. This would give charities the option to prioritize access to assistance based on clinical need – not simply the timing of the application for assistance. If such arrangements were permissible, a charitable patient assistance foundation could, for example, choose to prioritize assistance for a patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) whose care had proceeded in accordance with the guidelines of the American College of Rheumatology or for a patient with cancer who is appropriately receiving a targeted therapy given the presence of a particular biomarker. As a result, existing donor dollars might do more good for more patients. Ensuring that limited donor dollars buy as much health as possible could be worth the additional administrative expense associated with such an arrangement.

Conclusion

Advances in precision medicine have spurred calls for greater use of precision benefit design – benefit designs that encourage and enable patients to receive the right care, at the right time, in the right place, at an out-of-pocket price they can afford.13 Payers, purchasers, pharmacy benefit managers, patient assistance charities, and pharmaceutical manufacturers could find common ground by piloting precision patient assistance programs that complement these efforts. Through collaboration, stakeholders can steward limited health care resources while ensuring that out-of-pocket costs never prevent patients from accessing high-value therapies.

[a] This does not include Medicare beneficiaries who are also enrolled in Medicaid and those receiving the low-income subsidy.

University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design

The University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design (V-BID Center) is the leading advocate for development, implementation, and evaluation of clinically nuanced health benefit plans and payment models. Since 2005, the Center has been actively engaged in understanding the impact of innovative provider facing and consumer engagement initiatives, and collaborating with employers, consumer advocates, health plans, policy leaders, and academics to improve clinical outcomes and enhance economic efficiency of the U.S. health care system. For more information, find us at www.vbidcenter.org and follow us @UM_VBID.

Funding for this V-BID Center Brief was provided by Global Healthy Living Foundation

The Global Healthy Living Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization whose mission is to improve the quality of life for people living with chronic illnesses, such as arthritis, osteoporosis, migraine, diabetes, psoriasis, cardiovascular disease and chronic pain, by advocating for improved access to care at the community, state, and federal levels, and amplifying education and awareness efforts within its social media framework. GHLF is also a staunch advocate for vaccines. The Global Healthy Living Foundation is the parent organization of CreakyJoints, the go-to source for more than 100,000 arthritis patients and their families world-wide who are seeking education, support, advocacy and patient-centered research and ArthritisPower, the first ever patient-led, patient-centered research registry for arthritis, bone, and inflammatory skin conditions.

References

- Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, et al. Employer Health Benefits 2016. Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Research & Educational Trust, NORC at the University of Chicago; 2016:274. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-2016-Annual-Survey.

- Schoen C, Davis K, Willink A. Medicare Beneficiaries’ High Out-of-Pocket Costs: Cost Burdens by Income and Health Status.; 2017. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Issue-Briefs/2017/May/Medicare-Out-of-Pocket-Cost-Burdens. Accessed May 17, 2017.

- Hoadley J, Cubanski J, Neuman T. Medicare Part D: A First Look at Prescription Drug Plans in 2017. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2016. http://kff.org/report-section/medicare-part-d-a-first-look-at-prescription-drug-plans-in-2017-findings/. Accessed January 26, 2017.

- Newhouse JP, Insurance Experiment Group. Free for All?: Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996.

- Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298(1):61-69. doi:10.1001/jama.298.1.61.

- Eaddy MT, Cook CL, O’Day K, Burch SP, Cantrell CR. How patient cost-sharing trends affect adherence and outcomes: a literature review. P T Peer-Rev J Formul Manag. 2012;37(1):45-55.

- Brot-Goldberg ZC, Chandra A, Handel BR, Kolstad JT. What Does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-Sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2015. doi:10.3386/w21632.

- Wharam JF, Zhang F, Eggleston EM, Lu CY, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D. Diabetes outpatient care and acute complications before and after high-deductible insurance enrollment: a Natural Experiment for Translation in Diabetes (NEXT-D) Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):358. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8411.

- Wharam JF, Zhang F, Landon BE, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Low-socioeconomic-status enrollees in high-deductible plans reduced high-severity emergency care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(8):1398-1406. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1426.

- Reddy SR, Ross-Degnan D, Zaslavsky AM, Soumerai SB, Wharam JF. Impact of a high-deductible health plan on outpatient visits and associated diagnostic tests. Med Care. 2014;52(1):86-92. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000008.

- Rabin DL, Jetty A, Petterson S, Saqr Z, Froehlich A. Among low-income respondents with diabetes, high-deductible versus no-deductible insurance sharply reduces medical service use. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(2):239-245. doi:10.2337/dc16-1579.

- Chernew ME, Rosen AB, Fendrick AM. Value-based insurance design. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(2):w195-203. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.w195.

- Fendrick AM, Chernew ME. Precision benefit design—using “smarter” deductibles to better engage consumers and mitigate cost-related nonadherence. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):368-370. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8747.

- Lee JL, Maciejewski ML, Raju SS, Shrank WH, Choudhry NK. Value-based insurance design: quality improvement but no cost savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1251-1257. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0902.

- Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. A “Dynamic” Approach to Consumer Cost-Sharing for Prescription Drugs.; 2016. http://vbidcenter.org/a-dynamic-approach-to-consumer-cost-sharing-for-prescription-drugs/. Accessed May 11, 2017.

- Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Special Advisory Bulletin: Patient Assistance Programs for Medicare Part D Enrollees.; 2005. https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/2005/2005PAPSpecialAdvisoryBulletin.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2017.

- Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Supplemental Special Advisory Bulletin: Independent Charity Patient Assistance Programs.; 2014. https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/2014/independent-charity-bulletin.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2017.

- Enbrel® (etanercept) Financial Assistance. https://www.enbrel.com/support/financial-assistance/. Accessed March 26, 2017.

- Co‐pay Coupon | HARVONI® (ledipasvir 90 mg/sofosbuvir 400 mg). https://www.harvoni.com/support-and-savings/co-pay-coupon-registration. Accessed March 26, 2017.

- The LIPITOR® (atorvastatin calcium) Choice Card | Safety Info. LIPITOR. http://ssshare.it/pYiR. Published February 27, 2014. Accessed March 26, 2017.

- Wolinsky H. Drug companies ramp up use of coupons to battle generics. Modern Healthcare. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20160611/MAGAZINE/306119980. Published June 11, 2016. Accessed March 26, 2017.

- Starner CI, Alexander GC, Bowen K, Qiu Y, Wickersham PJ, Gleason PP. Specialty drug coupons lower out-of-pocket costs and may improve adherence at the risk of increasing premiums. Health Aff Millwood. 2014;33(10):1761-1769. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0497.

- Lee C, Grigorian M, Nolan R, Binder G, Rice G. A retrospective study of direct cost to patients associated with the use of oral oncology medications for the treatment of multiple myeloma. J Med Econ. 2016;19(4):397-402. doi:10.3111/13696998.2015.1130710.

- Daubresse M, Andersen M, Riggs KR, Alexander GC. Effect of prescription drug coupons on statin utilization and expenditures: a retrospective cohort study. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(1):12-24. doi:10.1002/phar.1802.

- Zullig LL, Wolf S, Vlastelica L, Shankaran V, Zafar SY. The role of patient financial assistance programs in reducing costs for cancer patients. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(4):407-411. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.4.407.

- Zafar Y, Asabere A, Bastian A. Oncology patient assistance programs (PAPs): A first-in-kind analysis of US drug manufacturer program benefits and eligibility requirements. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:S176. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(16)30517-2.

- GSKForYou | Patient Assistance Program. https://www.gskforyou.com/. Accessed March 26, 2017.

- Merck Programs to Help Those in Need – Home. http://www.merckhelps.com/. Accessed March 26, 2017.

- See How We Help | Pfizer RxPathways. . Accessed March 26, 2017.

- Office of Inspector General, US Department of Health and Human Services. Re: Modification of OIG advisory opinion 07-11. https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2015/mod-advopn0711.pdf. Published December 7, 2015. Accessed March 28, 2017.

- Pollack A. Co-pay coupons for patients, but higher bills for insurers. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/02/business/02coupon.html. Published January 1, 2011. Accessed March 27, 2017.

- Dafny LS, Ody CJ, Schmitt MA. Undermining value-based purchasing — lessons from the pharmaceutical industry. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(21):2013-2015. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1607378.

- Dafny L, Ody C, Schmitt M. When Discounts Raise Costs: The Effect of Copay Coupons on Generic Utilization. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2016. doi:10.3386/w22745.

- Ross JS, Kesselheim AS. Prescription-drug coupons — no such thing as a free lunch. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(13):1188-1189. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1301993.

- Flynn Kelly L. Can UnitedHealthcare’s new plan to block retail copay coupons work? AIS Health. Can UnitedHealthcare’s New Plan to Block Retail Copay Coupons … medicareissimple.blogspot.com/2014/…/can-unitedhealthcares-new-plan-to-block.htm…. Accessed March 27, 2017.

- Ornstein C. Drug coupons may save you money, but they’re keeping prices high. Here’s how. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2016/06/30/drug-coupons-may-save-you-money-but-theyre-keeping-drug-prices-high-heres-how/. Published June 30, 2016. Accessed March 26, 2017.

- Ubel PA, Bach PB. Copay assistance for expensive drugs: a helping hand that raises costs. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(12):878. doi:10.7326/M16-1334.

- Sanger-Katz M. Drug coupons: helping a few at the expense of everyone. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/13/upshot/drug-coupons-helping-a-few-at-the-expense-of-everyone.html. Published October 12, 2016. Accessed March 27, 2017.

- Silverman E. Bye, bye co-pay cards? Why Express Scripts is excluding dozens of drugs. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/edsilverman/2013/10/21/bye-bye-co-pay-cards-why-express-scripts-is-excluding-dozens-of-drugs/. Published October 21, 2013. Accessed March 27, 2017.

- Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. March 2017:annrheumdis-2016-210715. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715.

- Fendrick AM, Buxbaum J, Westrich K. Supporting Consumer Access to Specialty Medications through Value-Based Insurance Design. National Pharmaceutical Council and University of Michigan School of Public Health Center for Value-Based Insurance Design; 2014. http://vbidcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/vbid-specialty-medications-npc2014-final-web.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2017.