Outcomes-Based Contracting with Value-Based Insurance Design: Opportunities to Drive More Health per Pharmacy Dollar

Outcomes-Based Contracting with Value-Based Insurance Design: Opportunities to Drive More Health per Pharmacy Dollar

Background

Reimbursement that aligns spending with quality and patient-centered outcomes is widely viewed as a key enabler of achieving more value from the $3.7 trillion Americans spend annually on health care. For drugs, outcomes-oriented contracts – financial arrangements that tie payment to achieving pre-specified clinical goals – have received increasing attention. If structured correctly, these contracts have the potential to align the interests of patients, health plans, manufacturers, and society around the shared goal of ensuring prudent use of health care resources while preserving access to care and incentives for innovation.

The number of outcomes-oriented contracts is not known, since private plans and manufacturers do not have to publicly report their agreements. While some estimate that there are only 20 such agreements in effect, momentum for outcomes-oriented contracting is significant and growing.1 According to surveys of key industry leaders, 70 percent of polled payers have interest in outcomes-oriented contracting for pharmaceuticals, as do more than 60 percent of polled manufacturers.1,2 Key public purchasers have recently signaled interest in outcomes-oriented arrangements: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has announced its intent to develop an outcomes-oriented contract with Novartis for the CAR-T cell therapy Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and at least one state Medicaid program has broadcast its intention to develop pay-for-outcomes deals.3,4 Several prominent examples in the commercial sector – including a collaboration between Harvard Pilgrim and Spark Therapeutics to pay for a $850,000 gene therapy for inherited blindness through an outcomes-oriented arrangement – have also made headlines.5

The rise of targeted therapies for narrow patient populations has motivated some share of this growing interest: funds devoted to expensive breakthrough therapies such as gene therapies may be money very well-spent if patients respond to treatment. But given the heterogeneity of possible patient responses and the potential for benefits to accrue over long time periods – up to and including lifetimes – the current state of clinical knowledge may make it difficult or impossible to know before treatment which particular patients will ultimately benefit and which will not. Outcomes-oriented contracts offer an opening for payers to facilitate access in the absence of clinical certainty.

The rise of targeted therapies for narrow patient populations has motivated some share of this growing interest: funds devoted to expensive breakthrough therapies such as gene therapies may be money very well-spent if patients respond to treatment. But given the heterogeneity of possible patient responses and the potential for benefits to accrue over long time periods – up to and including lifetimes – the current state of clinical knowledge may make it difficult or impossible to know before treatment which particular patients will ultimately benefit and which will not. Outcomes-oriented contracts offer an opening for payers to facilitate access in the absence of clinical certainty.

As interest in outcomes-oriented arrangements spreads and new implementations are piloted, one critical player in these arrangements has tended to receive relatively little attention: the patient. After providing an overview on outcomes-oriented contracting, this brief offers a rationale for ensuring consumer perspectives and patient access figure prominently in the design of future agreements. The following sections will lay out suggestions for developing outcomes-oriented contracts that reflect the principles of value-based insurance design (V-BID) to ensure a patient-centered focus.

Developing Outcomes-Oriented Contracts

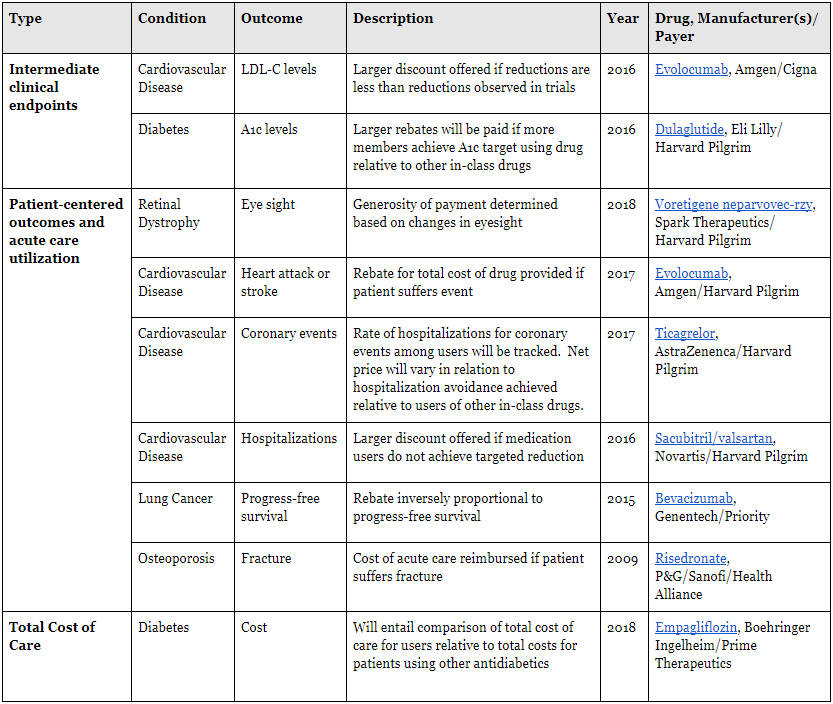

Executing a mutually advantageous outcomes-oriented contract requires agreement on the outcome of interest. As shown in the Table, there is precedent for targeting a range of specified outcomes. These include patient-centered outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular events), intermediate endpoints (e.g., HbA1c control), and the patient’s total cost of care.

Table: Examples of Outcomes-Oriented Payer/Manufacturer Arrangements for Drugs

The method of determining whether an outcome has been met is inherently related to the endpoint selected. For some endpoints, use of claims data is sufficient (e.g., occurrence of a cardiovascular event or a hospitalization). For other endpoints, structured data for intermediate outcomes of interest is already collected for purposes of quality reporting (e.g., HEDIS measures pertaining to diabetes control). For still other endpoints, such as progression-free survival, chart review – perhaps with the benefit of electronic health information exchange – may be necessary given the lack of clinical detail available in claims alone.6 Some see a role for third parties, such as specialty pharmacies, to serve as neutral arbiters of whether targeted outcomes have been achieved.7

How at-risk funds will flow must also be considered. Several approaches are possible. Adjusting the generosity of rebates for future medication fills is the most common approach (see Table). Manufacturers can also directly reimburse payers for potentially avoidable downstream utilization, e.g., re-hospitalizations or ED visits. Novartis, manufacturer of the treatment Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) has proposed a different approach: simply not charging for the cost of the therapy if the patient does not respond to treatment by the end of the first month.8 Most often, patient-facing incentives are not impacted.

Regulatory requirements can complicate the execution of these arrangements.9 In particular, the Medicaid Best Price Requirement dictates that state Medicaid programs must be offered the lower of (a) the lowest price (net of rebates) for which a given drug is sold on the commercial market, or (b) a discount of at least 23.1 percent off the list price. While it is important to note that the use of differing rebates to administer an outcomes-oriented arrangement could potentially set a new best price, Sachs et al have argued that – in most cases – the best price requirement need not prevent experimentation with outcomes-based contracts.10,11 A thorough treatment of other key regulatory issues, including off-label promotion of drugs and the federal anti-kickback statute, is available in a 2016 white paper.12

Value-Based Insurance Design

According to an April 2017 survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation, 63 percent of Americans believe that “lowering the amount individuals pay for health care” should be a top national priority.13 Furthermore, high cost-sharing for high-value health care medications and services is associated with many deleterious consequences. Hopes that shifting costs to consumers will help bring about smarter consumerism are simply not borne out by experience.14 The literature

is overwhelmingly clear that patients subject to greater cost-sharing tend to reduce use of services and medications – the greater the cost-share, the greater the corresponding reduction in service use.15–17 In response to across-the-board increases in cost-sharing, many studies find that patients reduce use of both high- and low-value care in similar proportions.15,18 Increased acute care utilization and poorer health outcomes may result.16,17,19,20 Research suggests that cost-related underuse of evidence-based services disproportionately impacts poorer Americans and those with chronic conditions.19–23 With the average deductible for self-only employer-sponsored coverage approaching $1,500 – and with high and rising cost-sharing even once any applicable deductible has been satisfied – cost-related non-adherence is a significant risk.24 Research suggests users of more expensive specialty drugs are especially likely to abandon their medications at their pharmacy counter.25

V-BID can reduce the risk of cost-related non-adherence. V-BID entails aligning patients’ out-of-pocket cost-sharing with the value of the underlying service – i.e., lowering cost-sharing for high-value services and/or increasing cost-sharing for low-value services. Such an approach encourages the use of high-value care while maintaining or strengthening incentives to avoid low-value spending.26 V-BID incorporates clinical nuance, “recognizing that the clinical benefit of a specific service or therapy depends on who receives it, who provides it, and where and when in the course of disease the service or therapy is provided.”27

A 2012 systematic review published in Health Affairs by Lee and colleagues identified thirteen studies of V-BID from the peer-reviewed literature, generally finding modest but meaningful improvements in adherence in association with reductions in cost-sharing. More recent research has produced similar findings.28–31

Incorporating V-BID Principles to Align Patient-Facing Incentives with Outcomes-Oriented Arrangements

As health sciences companies and payers design a new generation of financial arrangements, patient concerns about high out-of-pocket costs – and the cost-related nonadherence they may bring about – ought to remain at the forefront. At the same time, outcomes-oriented arrangements can provide a means for payers to safeguard against excessive expenditures for patients for whom the drug is not appropriate. While historically high cost-sharing has been justified by some as a means of reducing low-value expenditures, such rationale loses its salience in the context of an outcomes-oriented drug agreement.14 The outcomes-oriented reimbursement arrangement itself can serve this purpose. Ultimately, this should translate to patient-facing cost-sharing that is set at low, minimally burdensome levels. For the same reason, payers should ensure that utilization management protocols (e.g., prior authorization requirements) are minimally burdensome when meaningful outcomes-oriented arrangements are in effect.

As of January 2019, cost-sharing for seven million UnitedHealthcare members will reflect the plan-paid price, net of rebates – a potentially trend-setting move praised by Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar.32 In an ideal future state, the same dynamic cost-sharing adjustment might be used to ensure that patients’ financial responsibilities align with the principles underlying the outcomes-oriented arrangement. Even without dynamic cost-sharing, payers have moved glucose-lowering agents included in outcomes-based agreements to more preferred prescription drug formulary tiers.33 In many plans, differences between consumer cost-sharing for preferred and non-preferred drugs can vary by $100 or more, suggesting that these formulary tier adjustments may be highly meaningful to patients.34

These are precedents upon which expansion should be based.

Outcomes-oriented arrangements between payers and purchasers can go further than ameliorating the most burdensome elements of managed care. Depending on the nature of the mutually agreed-upon goal – improving blood sugar control, for instance – the patient might be offered a financial incentive for achieving well-defined targets. Adherence itself, the subject of many HEDIS and Medicare Advantage Stars performance measures, might be measured and incentivized by the plan or manufacturer. Such an approach would stand in contrast to one-size-fits-all cost-sharing for drugs that effectively obstructs adherence.

Outcomes-oriented arrangements can also provide a new opening for collaboration around care management and patient activation. For example, many patient assistance programs employ nurse care managers to monitor adherence. With shared incentives – e.g., the avoidance of disease exacerbation in rheumatoid arthritis – existing nurse care managers can broaden their focus beyond ensuring drug use and adherence toward ensuring optimal disease control more broadly. Such collaboration might include support for ensuring other needed care is received (e.g., diabetics’ foot care, eye care, etc.), support for addressing disease-relevant social determinants of health (e.g., linkages with key community resources), and support to build greater levels of patient activation more generally.35 With shared interests around patient-centered outcomes, the manufacturer/purchaser relationship might become less transactional and more patient-centered.

The complexity of executing outcomes-oriented reimbursement arrangements is partially responsible for the relatively small number of examples to-date. Recognizing the need for simplicity, the following principles are suggested for new payer-manufacturer agreements:

- Select drugs/conditions where the “juice is worth the squeeze.” This likely means focusing on high-cost specialty drugs or moderate-cost branded medications used to treat costly conditions – especially conditions where exacerbation is associated with high-cost outcomes.

- For low-volume, high-cost drugs, consider use of clinical data from medical charts in ascertaining outcomes (e.g., progression-free cancer survival). For high-volume/moderate-cost drugs, use only claims or clinical data that is already being collected for other purposes (e.g., emergency department visits for disease exacerbation, blood glucose control).

- Outcomes-oriented agreements should provide a “win” for targeted patients. Recognizing the centrality of adherence irrespective of the targeted outcome, cost-sharing should be set at minimally burdensome levels. If needed, manufacturers and payers should ensure financial assistance is available and that copay cards may be used without interference.36 Payers should move drugs covered by outcomes-oriented arrangements to more favorable formulary tiers.

From a societal perspective, additional important outcomes can only be ascertained by directly asking patients (e.g., pain control, function) or consulting non-health datasets (e.g., work attendance). At present, outcomes-oriented agreements that incorporate these endpoints are likely not practical, but such arrangements may merit consideration in future years.

Conclusion

Purchasers and health sciences companies should accelerate the movement to value-based reimbursement by giving strong consideration to outcomes-oriented arrangements for medications. Simultaneously, new outcomes-oriented agreements must recognize the central role of the patient.

University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design

The University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design (V-BID Center) is the leading advocate for development, implementation, and evaluation of clinically nuanced health benefit plans and payment models. Since 2005, the Center has been actively engaged in understanding the impact of innovative provider facing and consumer engagement initiatives, and collaborating with employers, consumer advocates, health plans, policy leaders, and academics to improve clinical outcomes and enhance economic efficiency of the U.S. health care system. For more information, find us at www.vbidcenter.org and follow us @UM_VBID.

Funding for this V-BID Center Brief was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim

Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., based in Ridgefield, CT, is one of the world’s top 20 pharmaceutical companies. Headquartered in Ingelheim, Germany, the company operates globally with approximately 50,000 employees. Since its founding in 1885, the company has remained family-owned and today creates value through innovation for three business areas including human pharmaceuticals, animal health and biopharmaceutical contract manufacturing.

Boehringer Ingelheim is committed to improving lives and providing valuable services and support to patients and their families. Our employees create and engage in programs that strengthen our communities. Please visit our website to learn more about how we make more health for more people through our Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives.

For more information please visit www.boehringer-ingelheim.us, or follow us on Twitter @BoehringerUS.

References

- Duhig A, Saha S, Smith S, Kaufman S, Hughes J. The Current Status of Outcomes-Based Contracting for Manufacturers and Payers: An AMCP Membership Survey. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. December 2017:1-6. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2017.16326

- Avalere Health. Health Plans Are Interested in Tying Drug Payments to Patient Outcomes.; 2016. http://avalere.com/expertise/life-sciences/insights/health-plans-are-interested-in-tying-drug-payments-to-patient-outcomes. Accessed March 8, 2018.

- Weintraub A. How to cover Novartis’ $475K CAR-T drug Kymriah? A ‘new payment model’ is the only way, Express Scripts says. FiercePharma. /financials/car-t-and-other-gene-therapies-need-new-payment-model-says-express-scripts. Published September 22, 2017. Accessed February 23, 2018.

- National Acdaemy for State Health Policy. NASHP Awards Grants to Colorado, Delaware, and Oklahoma to Tackle Rising Rx Drug Prices. https://nashp.org/nashp-awards-grants-to-colorado-delaware-and-oklahoma-to-tackle-rising-rx-drug-prices/. Published October 10, 2017. Accessed February 23, 2018.

- Beaton T. Outcomes-Based Contracts Offer Payers New Pharmaceutical Options. HealthPayerIntelligence. https://healthpayerintelligence.com/news/outcomes-based-contracts-offer-payers-new-pharmaceutical-options. Published January 10, 2018. Accessed March 8, 2018.

- Fox J, Watrous M. Overcoming Challenges Of Outcomes-Based Contracting For Pharmaceuticals: Early Lessons From The Genentech–Priority Health Pilot. Health Affairs. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/04/03/overcoming-challenges-of-outcomes-based-contracting-for-pharmaceuticals-early-lessons-from-the-genentech-priority-health-pilot/. Published April 3, 2017. Accessed March 8, 2018.

- Thomas J. The Challenge of Measuring Outcomes in Specialty Pharmacy. Specialty Pharmacy Times. https://www.specialtypharmacytimes.com/news/the-challenge-of-measuring-outcomes-in-specialty-pharmacy. Accessed February 24, 2018.

- Daniel G, Leschly N, Marrazzo J, McClellan M. Advancing Gene Therapies And Curative Health Care Through Value-Based Payment Reform. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20171027.83602/full/. Published October 30, 2017. Accessed February 24, 2018.

- Nussbaum S, Ricks D. Discovering New Medicines and New Ways to Pay for Them. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20160129.052814/full/. Published January 29, 2016. Accessed March 20, 2018.

- Sachs R, Bagley N, Lakdawalla DN. Innovative Contracting for Pharmaceuticals and Medicaid’s Best-Price Rule. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2018;43(1):5-18. doi:10.1215/03616878-4249796

- Sachs R, Bagley N, Lakdawalla DN. Value-Based Pricing For Pharmaceuticals In The Trump Administration. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170427.059813/full/. Published April 27, 2017. Accessed February 24, 2018.

- Pearson SD, Dreitlein B, Henshall C. Indication-Specific Pricing of Pharmaceuticals in the United States Health Care System. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review; 2015. http://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Final-Report-2015-ICER-Policy-Summit-on-Indication-specific-Pricing-March-2016_revised-icons.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2018.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health Tracking Poll – Late April 2017: The Future of the ACA and Health Care & the Budget.; 2017. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Topline-Kaiser-Health-TrackingPoll-Late-April-2017-The-Future-of-the-ACA-and-Health-Care-and-the-Budget. Accessed March 8, 2018.

- Capretta J. Compelling Evidence Makes the Case for a Market-Driven Health Care System. Washington, DC: The Heritage Foundation; 2013. https://www.heritage.org/health-care-reform/report/compelling-evidence-makes-the-case-market-driven-health-care-system. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- Newhouse JP, Insurance Experiment Group. Free for All?: Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996.

- Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298(1):61-69. doi:10.1001/jama.298.1.61

- Eaddy MT, Cook CL, O’Day K, Burch SP, Cantrell CR. How patient cost-sharing trends affect adherence and outcomes: a literature review. P T Peer-Rev J Formul Manag. 2012;37(1):45-55.

- Brot-Goldberg ZC, Chandra A, Handel BR, Kolstad JT. What Does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-Sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2015. doi:10.3386/w21632

- Wharam JF, Zhang F, Eggleston EM, Lu CY, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D. Diabetes outpatient care and acute complications before and after high-deductible insurance enrollment: a Natural Experiment for Translation in Diabetes (NEXT-D) Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):358. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8411

- Wharam JF, Zhang F, Landon BE, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Low-socioeconomic-status enrollees in high-deductible plans reduced high-severity emergency care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(8):1398-1406. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1426

- Wharam JF, Zhang F, Eggleston EM, Lu CY, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Effect of High-Deductible Insurance on High-Acuity Outcomes in Diabetes: A Natural Experiment for Translation in Diabetes (NEXT-D) Study. Diabetes Care. January 2018:dc171183. doi:10.2337/dc17-1183

- Reddy SR, Ross-Degnan D, Zaslavsky AM, Soumerai SB, Wharam JF. Impact of a high-deductible health plan on outpatient visits and associated diagnostic tests. Med Care. 2014;52(1):86-92. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000008

- Rabin DL, Jetty A, Petterson S, Saqr Z, Froehlich A. Among low-income respondents with diabetes, high-deductible versus no-deductible insurance sharply reduces medical service use. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(2):239-245. doi:10.2337/dc16-1579

- Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, et al. Employer Health Benefits 2016. Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Research & Educational Trust, NORC at the University of Chicago; 2016:274. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-2016-Annual-Survey.

- Starner CI, Alexander GC, Bowen K, Qiu Y, Wickersham PJ, Gleason PP. Specialty drug coupons lower out-of-pocket costs and may improve adherence at the risk of increasing premiums. Health Aff Millwood. 2014;33(10):1761-1769. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0497

- Chernew ME, Rosen AB, Fendrick AM. Value-based insurance design. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(2):w195-203. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.w195

- Fendrick AM, Chernew ME. Precision benefit design—using “smarter” deductibles to better engage consumers and mitigate cost-related nonadherence. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):368-370. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8747

- Yeung K, Basu A, Hansen R, Watkins J, Sullivan S. Impact of a Value-based Formulary on Medication Utilization, Health Services Utilization, and Expenditures. Med Care. 2017;55(2):191-198. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000630

- Hirth RA, Cliff EQ, Gibson TB, McKellar MR, Fendrick AM. Connecticut’s Value-Based Insurance Plan Increased The Use Of Targeted Services And Medication Adherence. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):637-646. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1371

- Choudhry NK, Bykov K, Shrank WH, et al. Eliminating Medication Copayments Reduces Disparities In Cardiovascular Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):863-870. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0654

- Maciejewski ML, Wansink D, Lindquist JH, Parker JC, Farley JF. Value-Based Insurance Design Program In North Carolina Increased Medication Adherence But Was Not Cost Neutral. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(2):300-308. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0260

- Morse S. UnitedHealthcare to pass drug rebates directly on to consumers. Health Care Finance. http://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/unitedhealthcare-pass-drug-rebates-directly-consumers. Published March 6, 2018. Accessed March 8, 2018.

- Staton T. Lilly’s Trulicity joins pay-for-performance trend with Harvard Pilgrim deal. FiercePharma. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/lilly-s-trulicity-joins-pay-for-performance-trend-harvard-pilgrim-deal. Published June 28, 2016. Accessed February 24, 2018.

- Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, Damico A, Foster G, Whitmore H. Employer Health Benefits 2017. Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Research & Educational Trust, NORC at the University of Chicago; 2017. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2017-employer-health-benefits-survey/.

- Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the Evidence Shows About Patient Activation: Better Health Outcomes and Care Experiences; Fewer Data on Costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):207-214. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061

- Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. Precision Patient Assistance Programs to Enhance Access to Clinically Indicated Therapies: Right Drug, Right Time, Right Cost-Share. Center for Value-Based Insurance Design; 2017. http://vbidcenter.org/precision-patient-assistance-programs-to-enhance-access-to-clinically-indicated-therapies-right-drug-right-time-right-cost-share/. Accessed March 8, 2018.