Narrow Networks and Value-Based Insurance Design

Executive Summary

Narrow networks aim to improve patient outcomes and increase quality of care by establishing a pool of providers to supply consumers with high-value, evidence-based care. This concept incorporates Value-Based Insurance Design (V-BID) principles, aligning patients’ out-of-pocket costs with the clinical value of services. However, narrow networks are often a source of confusion for consumers who may struggle to understand provider groups and performance metrics. Additionally, these value-based networks face the obstacle of ensuring an adequate network of providers for their patient population. Despite these challenges, narrow networks remain a promising alternative to traditional health coverage plans that may help contain costs, while improving patient outcomes.

Background

Narrow networks are a type of benefit design made popular by managed care organizations in the 1980s and 90s, and are gaining traction once again, in part due to the Affordable Care Act. Aimed at cost containment, narrow networks create smaller pools of in-network providers based on quality and cost data.

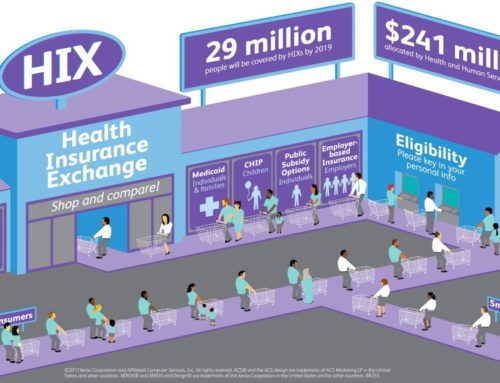

The ACA has spurred considerable growth in popularity of narrow networks due to the appeal of cheaper premiums to price-sensitive consumers. A study from McKinsey & Company found 70% of plans on the exchange in 2014 featured a limited network, with this composition remaining unchanged into 2015 [1]. Premiums for narrow networks are as much as 17% less expensive, compared to plans with broader networks [2]. The law includes a provision mandating insurers provide a minimum level of access to local providers, with a number of states exceeding these standards through their own discretion [3].

Narrow networks are not without drawbacks, as they offer consumers limited provider choice and may leave consumers vulnerable to the financial burden of out-of-network services not easily accessible within their plan’s network [4]. Consumers must also take special care to thoroughly understand what their plan does and does not cover. Insufficient regulatory oversight and inadequate plan transparency may leave consumers without the knowledge required for making informed decisions [5].

What is Value-Based Insurance Design?

Value-Based Insurance Design (V-BID) is a benefit design strategy built on the principle of lowering or removing financial barriers to essential, high-value clinical services. V-BID plans align patients’ out-of-pocket costs, such as copayments, with the value of services. These innovative products are designed with the tenets of ‘clinical nuance’ in mind. These tenets recognize that 1) medical services differ in the amount of health produced, and 2) the clinical benefit derived from a specific service depends on the consumer using it, as well as when, where, and by whom the service is provided.

Narrow Networks and V-BID

Narrow networks were originally formed to decrease costs by creating smaller pools of in-network providers based on quality and cost data. Payers encourage consumers to seek out these preferred providers by providing financial incentives. A new vision of narrow networks incorporates value-based insurance design using incentives to steer consumers to high-performing, high-value providers. In this set-up, patient out-of-pocket costs are lower, as cost-sharing is aligned with the value of the care they receive from these providers. However, if the consumer elects to see a lower quality provider, they will bear a higher portion of the costs.

By aligning patient needs with high quality providers, payers benefit through improved patient outcomes and, in some instances, lower total costs. Managed care organizations such as HealthNet, Aetna, and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care have begun developing narrow networks to achieve these aims. Aetna expects that these narrow networks will result in a 1-4% decrease in costs compared to current traditional plans, while HealthNet of Arizona expects a 10-20% decrease [6]. Using benefit design to steer people towards high-performing providers compliments traditional V-BID programs that encourage the use of high-value services and providers.

These synergies are most evident in plans that are tailored for specific chronic diseases. Aetna and UnitedHealthcare have debuted private plans that directly address disease management in patients with prediabetes and diabetes. These plans provide more comprehensive coverage of diabetes services, including medication and equipment, if the beneficiary chooses an in-network provider. They also significantly decrease, if not completely eliminate, copays or out-of-pocket costs in order to encourage better management and medication adherence. By incorporating the V-BID concept of clinical nuance into their program offerings, insurers are improving patient access to diabetes specialists, which results in better long-term health outcomes and potentially lower costs [8].

Moving forward

Narrow networks — based on quality and cost measures — pose a promising means of aligning patient and provider incentives to achieve improved quality and enhanced consumer experience, while lowering healthcare costs. However, these value-based networks face obstacles, partially due to definition and implementation, that need to be addressed before this notion can be widely accepted and adopted.

Many consumers report having difficulty understanding their health coverage options in traditional plans. Having to navigate provider groups in a tiered narrow network plan has the potential to increase their confusion. Additionally, narrow networks are burdened by a constant stream of bad press. This model is often construed as a means to limit choice, rather than provide high quality care [4; 9; 10]. This makes choosing appropriate health insurance coverage even more perplexing, consequently making narrow networks more difficult to gain public acceptance from both consumers and policymakers [4]. To address this obstacle, robust education efforts will be needed to help demystify what narrow networks are and how they could benefit consumers.

In addition to emphasizing the value and quality improvements gained from narrow networks, insurance plans that implement these networks will need to provide incentives to keep consumers in the plans. Price-conscious consumers may be tempted to switch plans before they (and the plan) can reap the health benefits and financial return from the upfront investment made by these narrow networks. Therefore, plans will need to help align consumers’ needs with high quality providers by incentivizing consumers to stay in these narrow network plans.

To ensure that a network continues to meet its goals, adequate network protection is needed. There must be a sufficient number of providers in the network to keep costs low and value high. Otherwise, narrow networks will end up barring consumers from accessing necessary care. Additionally, when applying narrow networks broadly, payers will need to consider characteristics of their consumer base when establishing a provider network. To deliver high-value care, these networks will need to consider the health concerns of their target populations. There are definite challenges in creating a network to cater to certain patients, such as those with multiple chronic conditions [4].

Conclusion

Quality driven, narrow networks, provide the U.S. healthcare system with a potential model to improve patient outcomes by engaging both consumers and providers, with the potential to enhance quality and decrease healthcare costs. Consumers are able to access high-value, evidence-based care at a lower, more affordable price than traditional health plans.

However, improving acceptance and uptake of the narrow networks concept will require network architects to conduct extensive consumer outreach to clarify the incremental benefits of these value-based networks over the status quo. Additionally, systems will need to be established to ensure that the goals of these networks are sustainable with different patient mixes and in different locations.

References:

- Bauman, N., Bello, J., Coe, E., and Parkih, A. “Hospital networks: Evolution of the configurations on the 2015 exchanges.” http://healthcare.mckinsey.com/2015-hospital-networks McKinsey & Company. Published April 2015.

- http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20150328/MAGAZINE/303289988

- http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2014/feb/narrows-networks-boon-or-bane

- http://www.pnhp.org/news/2015/april/academyhealth-brief-on-the-sad-status-of-narrow-networks

- Corlette (2014). http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2014/rwjf413643

- Burns, J. “Narrow Networks Found to Yield Substantial Savings.” https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22393601/ Managed Care. Published February 2012.

- National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). http://www.nber.org/papers/w20462

- KHN. “New health plans offer discounts for diabetes care.” http://khn.org/news/new-health-plans-offer-discounts-for-diabetes-care/

- RWJF. “Take Two Aspirin.” http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2014/07/take-two-aspirin.html

- Sanger-Katz, M. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/10/upshot/narrow-health-networks-maybe-theyre-not-so-bad.html?_r=0