Cost-Sharing for Immunizations in Medicare: Impacts on Beneficiaries and Recommendations for Policymakers

Cost-Sharing for Immunizations in Medicare: Impacts on Beneficiaries and Recommendations for Policymakers

Introduction

Vaccine-preventable diseases affecting adults cost the US nearly $9 billion per year, including $5.9 billion in inpatient costs alone.1 Yet rates of vaccination among adults remain stubbornly low, with a 2012 report suggesting more than 20 million Medicare beneficiaries have not received vaccinations in accordance with evidence-based guidelines.2 Specifically, in 2014:

• 28 percent of Americans age 65 and older were not vaccinated for influenza,

• 38 percent of Americans age 65 and older were not vaccinated for pneumococcal disease, and

• 69 percent of Americans age 65 and older were not vaccinated for herpes zoster.3

Given the high-value of immunizations and the substantial room for improvement with vaccine compliance, the Healthy People 2020 goals include numerous objectives dedicated to increasing receipt of evidence-based immunizations – including the percentage of adults vaccinated against influenza, pneumococcal disease, and herpes zoster, as well as increasing the percentage of high-risk adults immunized against hepatitis B.4

The vast majority of Americans with commercial health insurance coverage in 2017 are currently guaranteed access to all age-appropriate vaccinations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) without consumer cost-sharing. However, Medicare beneficiaries face varying levels of cost-sharing for select ACIP-recommended vaccines. These differences in beneficiary cost-sharing are not grounded in clinical effectiveness. Recognizing the need to improve rates in vaccine uptake, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has encouraged Medicare Part D plans to offer more generous coverage for Part D-covered recommended immunizations.5,6 Yet high out-of-pocket costs persist for some evidence-based vaccinations.

This brief addresses the policy context of coverage and cost-sharing for vaccines in the Medicare program, the impact of beneficiary cost-sharing on vaccine uptake, and recommendations for policymakers to implement cost-sharing vaccine strategies to better protect the health of Medicare beneficiaries.

Coverage and Cost-Sharing for Vaccines in Medicare

1965 through Medicare Modernization Act of 2003

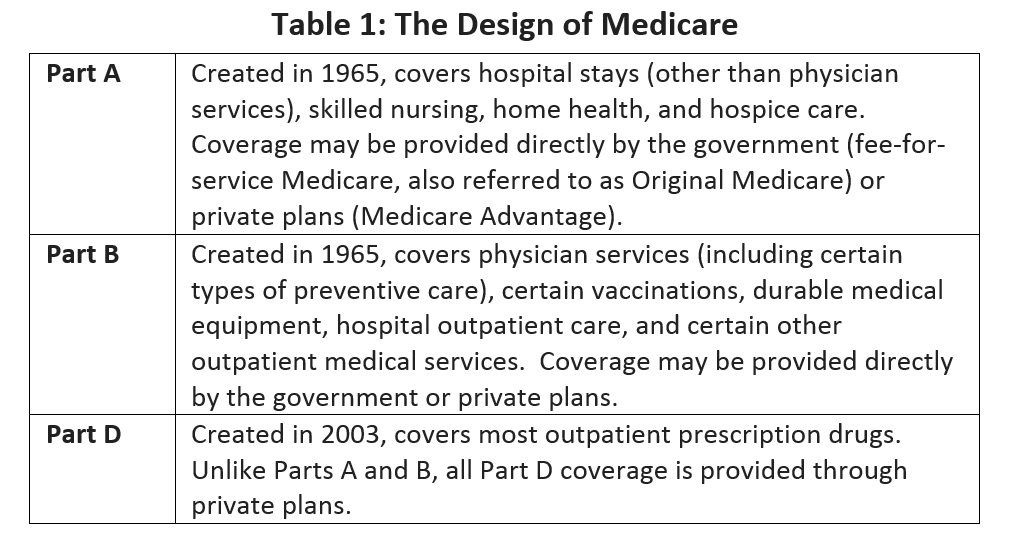

As originally enacted in 1965, the Medicare program generally did not provide coverage[a] for drugs or vaccinations. An exception was made for outpatient coverage of physician-administered drugs in Medicare Part B, out of concern that without this exception, physicians might hospitalize patients in order to obtain coverage through Medicare Part A.7,8 The breadth of Part B coverage – for vaccines and other services – evolved considerably between 1965 and 2003. On the eve of passage of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA), Part B provided coverage – with consumer cost-sharing – of more than 450 drugs,7 including vaccinations for pneumococcal pneumonia, influenza, and hepatitis B (for individuals at high or intermediate risk of contracting hepatitis B).2 The features of Medicare Parts A, B, and D are reviewed in Table 1.

In general, fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with Part B coverage who have satisfied the Part B deductible are responsible for 20% of Medicare’s allowed amount for all Part B-covered physician-administered drugs[b].

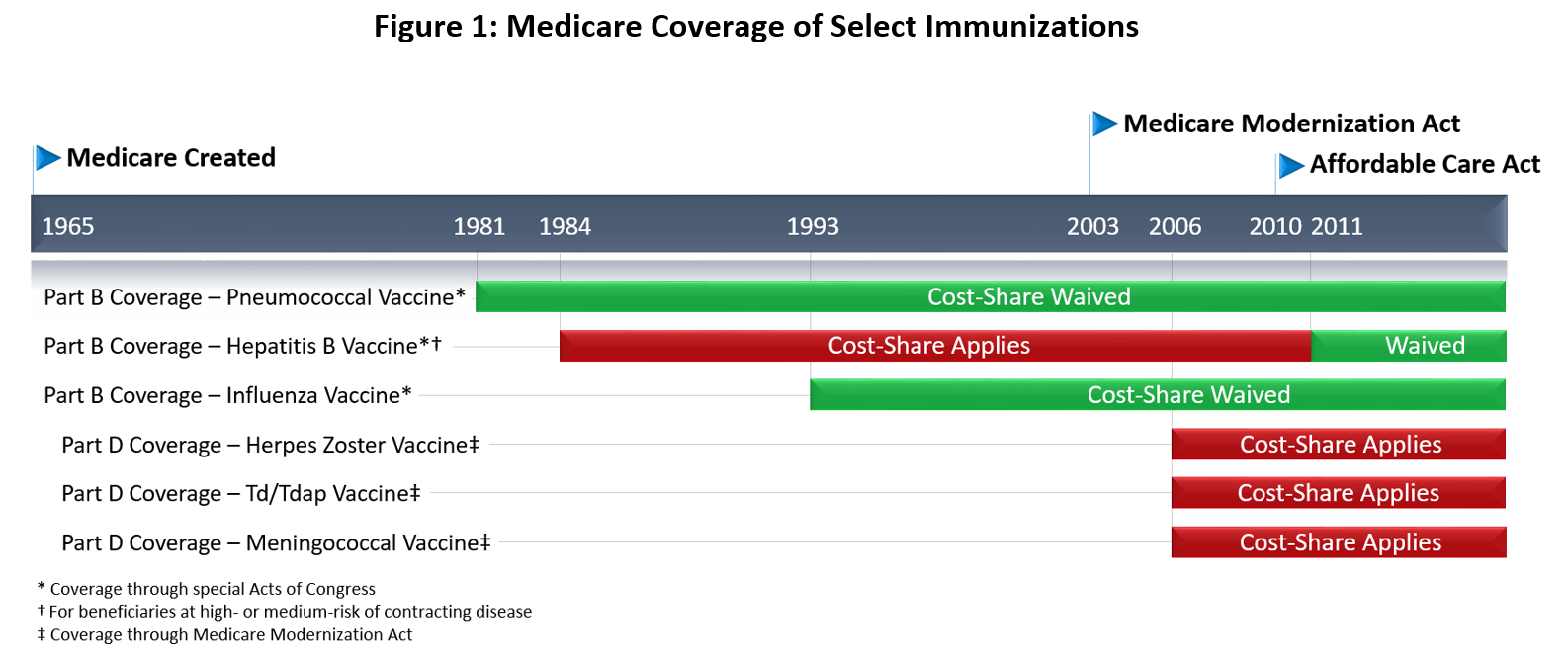

Specific exceptions were made for the pneumococcal vaccination in 1981 and the influenza vaccination in 1993, which were (and remain) covered without beneficiary cost-sharing.9 (Figure 1)

Medicare Modernization Act

The enactment of the MMA in 2003 transferred responsibility for most Medicare prescription drug spending to subsidized Part D plans. In doing so, the MMA took care not to disturb existing coverage under Part B, including Part B-covered vaccinations. Section 101 of the MMA, codified at 42 USC 1395w-102, amended the Social Security Act to provide:

A drug prescribed for a part D eligible individual that would otherwise be a covered part D drug under this part shall not be so considered if payment for such drug as so prescribed and dispensed or administered with respect to that individual is available (or would be available but for the application of a deductible) under part A or B for that individual.

The implication of this provision is that vaccinations “directly related to the treatment of an injury or direct exposure to a disease or condition” remain the responsibility of Part B.10 Vaccinations that were covered by Part B at the time of the enactment of the MMA also remain Part B drugs. All other commercially available vaccinations that are medically necessary to prevent illness are generally covered through Medicare Part D.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

Section 1001 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) created a Section 2713 of the Public Health Service Act (“Coverage of Preventive Health Services”) requiring non-grandfathered commercial health plans to cover, without consumer cost-sharing, grade A or B services recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). The new Section 2713 also required non-grandfathered commercial health plans to cover all age-appropriate vaccinations recommended by the ACIP. Non-grandfathered health plans must cover these services and vaccinations subject to reasonable medical management techniques (e.g., requirements to use in-network providers).

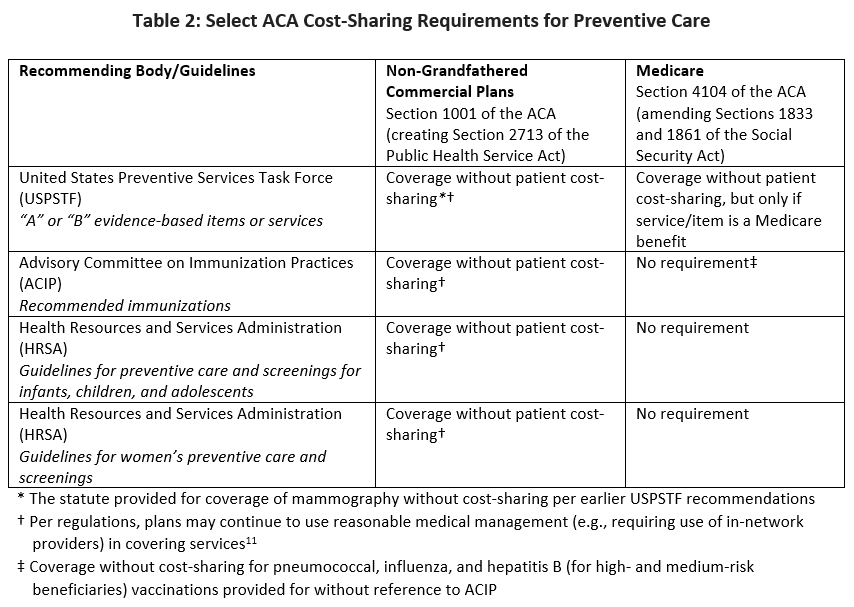

Section 4104 of the ACA, “Removal of Barriers to Preventive Services in Medicare,” in some respects, provides similar protection against cost sharing for Medicare beneficiaries. The text of this section makes extensive cross-references to various portions of Medicare law as codified in the Social Security Act. In pertinent part, Section 4104 provides coverage for certain preventive services that were previously delineated in the Social Security Act with no beneficiary cost-share, so long as the services carry a USPSTF A or B recommendation. The ACA also provided a process by which the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services may update the Medicare benefits structure as to provide coverage without cost-sharing for new USPSTF recommended services (even if such services were not previously Medicare benefits). Unlike Section 1001, which eliminates consumer cost-sharing for ACIP recommended-vaccinations in non-Medicare health insurance plans, Section 4104 does not explicitly require zero-dollar cost-sharing for Medicare beneficiaries when receiving age-appropriate vaccinations recommended by the ACIP. However, Part B-covered vaccinations (i.e., pneumococcal, influenza, and hepatitis B for individuals at high- or medium-risk) were previously delineated as covered preventive services in the statue as described above. Of these, pneumococcal and influenza vaccines were already covered without cost-sharing. Thus, with the exception of the hepatitis B vaccine – which is now available to high- and medium-risk beneficiaries without cost-sharing – Section 4104 did not eliminate consumer cost-sharing for ACIP-recommended vaccines. (Table 2)

Therefore, despite the title of the section – “removal of barriers to preventive services in Medicare” – and the apparent parallels to Section 1001/2713, Section 4104 provided comparatively less protection from cost sharing for Medicare beneficiaries than those enrolled in non-Medicare health plans. The ultimate effect is that individuals over age 65 now generally receive less generous immunization benefits than benefits provided to individuals under age 65 – despite their high clinical benefit from these preventive care services. Since it is unlikely that Congress would have intended such an outcome, it appears that the intended spirit of the ACA’s cost-sharing protections for vaccine use was not achieved.

Implications for Access

It is critical to emphasize that distinctions between Part B vaccination coverage and Part D vaccination coverage, and corresponding protections against cost-sharing, do not relate to clinical effectiveness. Rather, these distinctions are better understood as artifacts of statutory history and the complexity of Medicare law. The implications of differential cost-sharing strategies are noteworthy, and these impacts may be significant with respect to both patient-centered outcomes and total costs of care.

Differences in Medicare Cost-Sharing for ACIP Recommended Vaccines

A February 2016 report released by Avalere Health reported that all stand-alone Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Plans (PDPs) require cost-sharing for Part D-covered immunizations, as do most Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug Plans (MA-PDPs), accounting for 88% of MA-PDP enrollment.12 Although CMS suggested that reductions in cost-sharing for recommended vaccines are warranted in two recent Part D call letters,5,6 the amount of cost-sharing varies considerably by plan. On average, beneficiaries not receiving the low-income subsidy are typically subject to cost sharing of between $42 and $54 per Part D vaccination (for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug Plans) or $14 and $102 (for beneficiaries in stand-alone PDPs). Herpes zoster vaccination tends to have the highest cost sharing, with a typical copayment of more than $50.12 As detailed above, the three Part B-covered vaccinations are not subject to Part D cost-sharing.

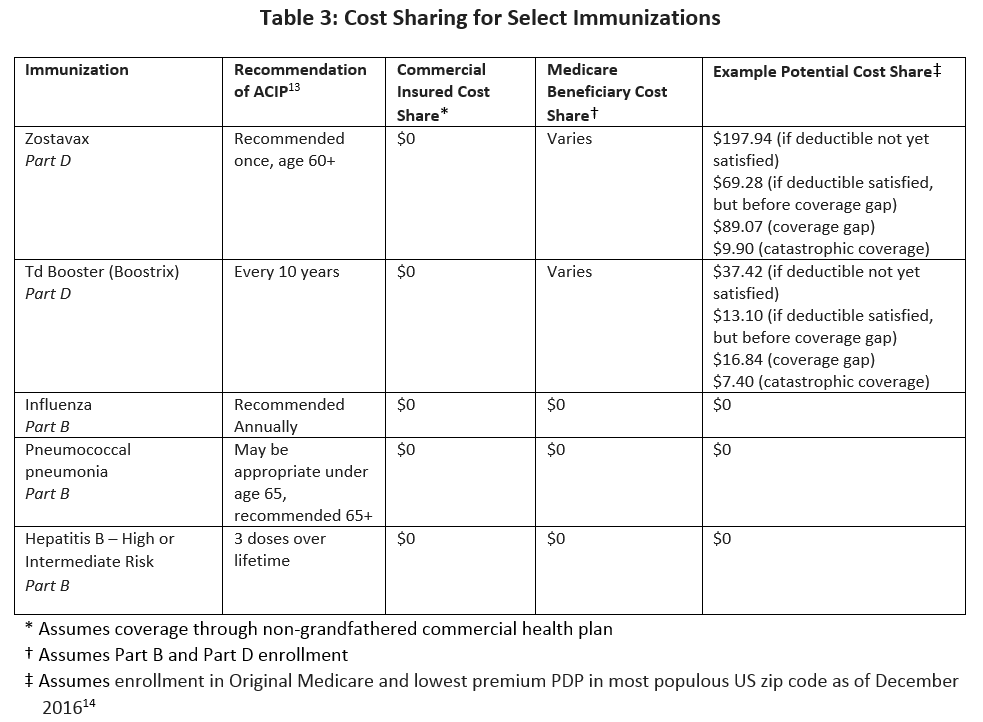

Table 3 illustrates the differences in how ACIP-recommended vaccinations for adults are covered in non-grandfathered commercial health plans relative to Medicare beneficiaries with Part B and Part D coverage.

Literature on Impact of Consumer Cost-Sharing on Vaccine Use

A rich body of literature clearly indicates that increasing consumer cost-sharing for high-value services tends to decrease the receipt of those services by Medicare beneficiaries, especially among poorer beneficiaries and those with multiple chronic clinical conditions.15 The literature is also clear that the ACA’s elimination of beneficiary cost-sharing for many preventive services has generally increased receipt of those services, with positive implications for socioeconomic disparities.16–22

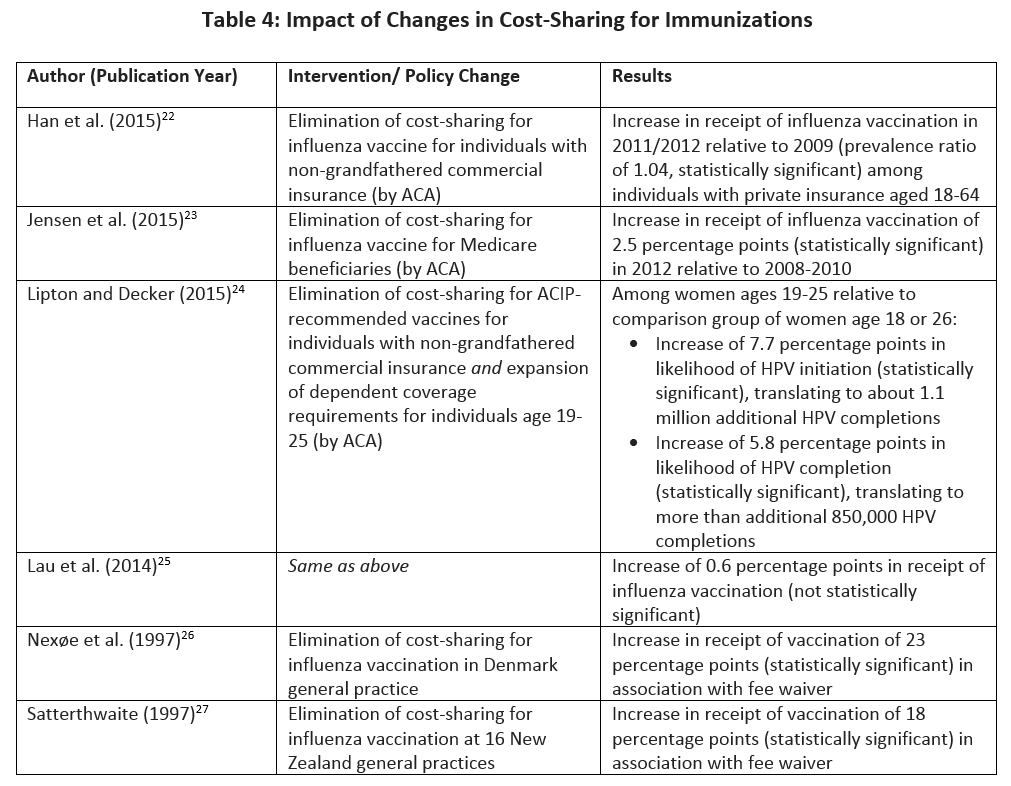

While the published literature on immunizations and cost-related nonadherence is more limited, it is reasonable to assume that the impact of beneficiary cost-sharing on service receipt is little different than the impact of cost-sharing on receipt of preventive services more generally. Table 4 summarizes results from six studies on cost-sharing for immunizations.22–27 (Two reflect changes in vaccination receipt corresponding to both reductions in cost-sharing and increases in health insurance coverage.24,25)

Perceptions among clinicians confirm that increasing levels of consumer cost-sharing can interfere with receipt of Part D-covered vaccinations. According to 2010 surveys from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), 69% of pharmacies not stocking the herpes zoster immunization cited beneficiaries’ difficulty affording the cost-sharing for the vaccination as influencing their decision, as did 86% of physicians not stocking the vaccination.2 The GAO data suggest that these decisions not to stock – in part due to concerns about limited uptake given beneficiary cost-sharing – are common: only 31% of physician offices stock the herpes zoster vaccination, even as more than 90% of physician offices stock the pneumococcal vaccination. Pharmacies are similarly less likely to stock the zoster vaccination.

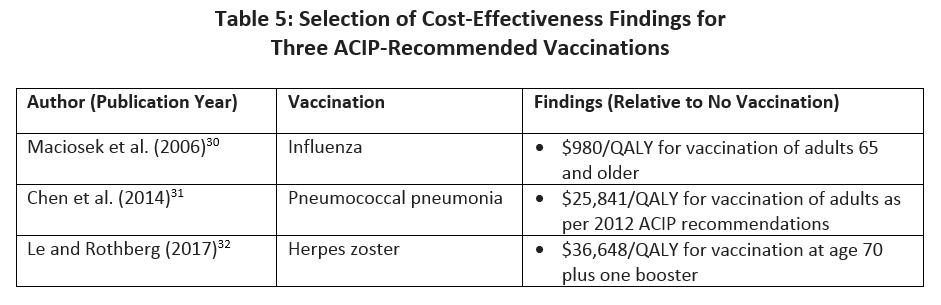

When administered in accordance with ACIP guidelines, the value of immunizations is high: the price of one quality-adjusted life year (QALY, a measure used in determining cost-effectiveness) obtained through vaccination is often far less the cost per QALY of many other common medical services and interventions. As shown in Table 5, researchers have found costs per QALY that are competitive with other recommended preventive services,28,29 and less than the commonly accepted threshold of $100,000 per QALY. Apart from cost effectiveness analysis, researchers have estimated that the 18 million vaccine-preventable cases of influenza, pneumococcal pneumonia, and herpes zoster each year lead to $5.8 billion in inpatient costs, $2.1 billion in outpatient costs, and $235 million in medication costs.1

Implications and Recommendations

Consumer cost-sharing for selected Part D-covered vaccinations contributes to sub-optimal vaccination rates for high-value ACIP-recommended immunizations that have been demonstrated to reduce morbidity and mortality. The tenants of value-based insurance design – which emphasize the need to align consumer cost-sharing with clinical benefit – would suggest that cost-sharing must be minimal for these vaccinations – especially for those patient populations who are likely to benefit the most from their use.

Accordingly, policymakers should seek opportunities to address differences in consumer cost-sharing that are artifacts of statutory history rather than reflections of differences in clinical importance. Implications of the available peer-reviewed literature clearly support the elimination of cost sharing for Medicare beneficiaries receiving immunizations recommended and used in accordance with the ACIP guidelines. To this end, policymakers should seek to ensure that the immunization coverage received by 65-year-old Americans is no less generous than the full coverage received by younger Americans.

Policy options to address cost-related barriers to receipt of immunizations among Medicare beneficiaries include:

- CMS should continue to encourage Part D plan sponsors to voluntarily cover vaccinations with $0 or minimal cost-sharing.[c],5,6 CMS might strengthen such encouragement by adjusting the plan finder algorithm as to favor PDPs that implement high-value benefit designs that vary cost-sharing on clinical importance rather than simply acquisition costs. Generous coverage for ACIP-recommended immunizations would be a hallmark of high-value benefit designs.

- At present, the stars system for Medicare Prescription Drug plans includes a measure of influenza vaccination receipt. Receipt of pneumococcal vaccination is reported as a “display-only” measure, but not included in the stars measures. In consultation with key stakeholders, CMS should consider including receipt of both Part B and Part D-covered ACIP-recommended immunizations in the Stars formula under the “Staying Healthy” stars domain.33

- At present, the stars system for Medicare Prescription Drug plans includes measures related to member experience and customer service, as well as several measures related to chronic disease medication adherence and medication safety. There are no stars measures pertaining to receipt of receipt of Part D-covered ACIP-recommended immunizations. Since Part D-only plans lack the total-cost-of-care accountability of Medicare Advantage plans – accountability that appears to encourage more generous coverage of evidence-based, utilization-averting immunizations12 – prevention-oriented quality measures are especially critical in this context. In consultation with key stakeholders, CMS should remedy the highly problematic lack of appropriate incentives through updates to the Part D star system.33

Conclusion

More than 3.7 million cases per year of vaccine-preventable illnesses occur among American adults age 65 and older.1 Influenza, pneumococcal, and herpes zoster vaccination account for the vast share of these cases, but only the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are routinely available without cost-share to Medicare beneficiaries. As new immunizations become available under Part D, current policy that permits plans to impose substantial consumer cost-sharing will hinder uptake of new and existing high-value Part D vaccinations alike. Changes in federal policy to better align cost-sharing levels with the clinical value to the patient or to society at large can ensure that MA-PDs and PDPs have the right incentives to keep their members healthy, reduce the incidence of preventable disease, and avert downstream health care costs.

[a] Unless otherwise indicated, the term “coverage” does not necessarily indicate first-dollar coverage, i.e., coverage may be offered with or without beneficiary cost-sharing.

[b] Many patients may not pay cost-sharing in this form or this amount, however, given enrollment in Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, or supplemental coverage.

[c] The language reads as follows:

Despite ACIP recommendations and Healthy People 2020 targets, adult immunization rates still remain low. We encourage Part D sponsors to consider offering $0 or low cost-sharing for vaccines to promote this important benefit. While the inclusion of a dedicated vaccine tier or a Select Care/Select Diabetes tier that contains vaccine products as part of a 5 or 6 tier formulary structure is not a requirement, sponsors who choose to offer one of these formulary tiers must set the cost-sharing at $0 for that tier.

References

- Ozawa S, Portnoy A, Getaneh H, Clark S, Knoll M, Bishai D, Yang HK, Patwardhan PD. Modeling The Economic Burden Of Adult Vaccine-Preventable Diseases In The United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2124-2132. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0462.

- Government Accountability Office. Medicare: Many Factors, Including Administrative Challenges, Affect Access to Part D Vaccinations. 2011;(GAO-12-61). http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-61. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Williams WW, Lu P-J, O’Halloran A, Kim DK, Grohskopf LA, Pilishvili T, Skoff TH, Nelson NP, Harpaz R, Markowitz LE, Rodriguez-Lainz A, Bridges CB. Surveillance of Vaccination Coverage Among Adult Populations — United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(1):1-36. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6501a1.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotin. Immunization and Infectious Diseases | Healthy People 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) 2016 Medicare Advantage Capitation Rates and Medicare Advantage and Part D Payment Policies and Final Call Letter.; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2016.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) 2017 Medicare Advantage Capitation Rates and Medicare Advantage and Part D Payment Policies and Final Call Letter.; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2017.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Oliver TR, Lee PR, Lipton HL. A Political History of Medicare and Prescription Drug Coverage. Milbank Q. 2004;82(2):283-354. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00311.x.

- Megellas MM. Medicare Modernization: The New Prescription Drug Benefit and Redesigned Part B and Part C. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2006;19(1):21-23.

- Goodwin SM, Anderson GF. Effect of Cost-Sharing Reductions on Preventive Service Use Among Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2(1). doi:10.5600/mmrr.002.01.a03.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Vaccine and Vaccine Administration Payments Under Medicare Part D.; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Vaccines-Part-D-Factsheet-ICN908764.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight. Affordable Care Act Implementation FAQs – Set 12. CMS; 2013. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/aca_implementation_faqs12.html. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Avalere Health. Adult Vaccine Coverage in Medicare Part D Plans.; 2016. http://go.avalere.com/acton/attachment/12909/f-0297/1/-/-/-/-/20160217_Medicare%20Vaccines%20Coverage%20Paper.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Kim DK, Riley LE, Harriman KH, Hunter P, Bridges CB, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older, United States, 2017. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(3):209. doi:10.7326/M16-2936.

- Humana Medicare – Walmart Prescription Drug Plan. . Accessed February 24, 2017.

- Fendrick AM, Oesterle SL, Lee HM, Padaley P, Eagle T, Chernew M, Mueller PP, Adams J, Agostini JV, Montagano C. Incorporating Value-Based Insurance Design to Improve Chronic Disease Management in the Medicare Advantage Program. Weat Health Policy Center and University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design; 2016. http://vbidcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/MA-White-Paper_final-8-16-16.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2017.

- Jena AB, Huang J, Fireman B, Fung V, Gazelle S, Landrum MB, Chernew M, Newhouse JP, Hsu J. Screening Mammography for Free: Impact of Eliminating Cost Sharing on Cancer Screening Rates. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(1):191-206. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12486.

- Sabatino SA, Thompson TD, Guy GP, de Moor JS, Tangka FK. Mammography Use Among Medicare Beneficiaries After Elimination of Cost Sharing. Med Care. 2016;54(4):394-399. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000495.

- Cooper GS, Kou TD, Schluchter MD, Dor A, Koroukian SM. Changes in Receipt of Cancer Screening in Medicare Beneficiaries Following the Affordable Care Act. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5). doi:10.1093/jnci/djv374.

- Hamman MK, Kapinos KA. Affordable Care Act Provision Lowered Out-Of-Pocket Cost And Increased Colonoscopy Rates Among Men In Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(12):2069-2076. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0571.

- Richman I, Asch SM, Bhattacharya J, Owens DK. Colorectal Cancer Screening in the Era of the Affordable Care Act. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):315-320. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3504-2.

- Fedewa SA, Goodman M, Flanders WD, Han X, Smith RA, M. Ward E, Doubeni CA, Sauer AG, Jemal A. Elimination of cost-sharing and receipt of screening for colorectal and breast cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(18):3272-3280. doi:10.1002/cncr.29494.

- Han X, Robin Yabroff K, Guy Jr. GP, Zheng Z, Jemal A. Has Recommended Preventive Service Use Increased After Elimination of Cost-Sharing as Part of the Affordable Care Act in the United States? Prev Med. 2015;78:85-91. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.012.

- Jensen GA, Salloum RG, Hu J, Ferdows NB, Tarraf W. A Slow Start: Use of Preventive Services Among Seniors Following the Affordable Care Act’s Enhancement of Medicare Benefits in the U.S. Prev Med. 2015;76:37-42. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.023.

- Lipton BJ, Decker SL. ACA Provisions Associated With Increase In Percentage Of Young Adult Women Initiating And Completing The HPV Vaccine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(5):757-764. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1302.

- Lau JS, Adams SH, Park MJ, Boscardin WJ, Irwin CE. Improvement in Preventive Care of Young Adults After the Affordable Care Act: The Affordable Care Act Is Helping. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(12):1101. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1691.

- Nexøe J, Kragstrup J, Rønne T. Impact of Postal Invitations and User Fee on Influenza Vaccination Rates Among the Elderly. a Randomized Controlled Trial in General Practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1997;15(2):109-112.

- Satterthwaite P. A Randomised Intervention Study to Examine the Effect on Immunisation Coverage of Making Influenza Vaccine Available at No Cost. N Z Med J. 1997;110(1038):58-60.

- Black WC, Gareen IF, Soneji SS, Sicks JD, Keeler EB, Aberle DR, Naeim A, Church TR, Silvestri GA, Gorelick J, Gatsonis C. Cost-Effectiveness of CT Screening in the National Lung Screening Trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1793-1802. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312547.

- Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Brenner H. Cost-Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33(1):88-100. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxr004.

- Maciosek MV, Solberg LI, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Goodman MJ. Influenza Vaccination Health Impact and Cost Effectiveness Among Adults Aged 50 to 64 and 65 and Older. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):72-79. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.008.

- Chen J, O’Brien MA, Yang HK, Grabenstein JD, Dasbach EJ. Cost-Effectiveness of Pneumococcal Vaccines for Adults in the United States. Adv Ther. 2014;31(4):392-409. doi:10.1007/s12325-014-0115-y.

- Le P, Rothberg MB. Determining the Optimal Vaccination Schedule for Herpes Zoster: a Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):159-167. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3844-6.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Part C and D Performance Data. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/PerformanceData.html. Published February 2, 2017. Accessed February 25, 2017.

Funding for this V-BID Center Brief was provided by PhRMA.

Introduction

Introduction

Vaccine-preventable diseases affecting adults cost the US nearly $9 billion per year, including $5.9 billion in inpatient costs alone.1 Yet rates of vaccination among adults remain stubbornly low, with a 2012 report suggesting more than 20 million Medicare beneficiaries have not received vaccinations in accordance with evidence-based guidelines.2 Specifically, in 2014:

• 28 percent of Americans age 65 and older were not vaccinated for influenza,

• 38 percent of Americans age 65 and older were not vaccinated for pneumococcal disease, and

• 69 percent of Americans age 65 and older were not vaccinated for herpes zoster.3

Given the high-value of immunizations and the substantial room for improvement with vaccine compliance, the Healthy People 2020 goals include numerous objectives dedicated to increasing receipt of evidence-based immunizations – including the percentage of adults vaccinated against influenza, pneumococcal disease, and herpes zoster, as well as increasing the percentage of high-risk adults immunized against hepatitis B.4

The vast majority of Americans with commercial health insurance coverage in 2017 are currently guaranteed access to all age-appropriate vaccinations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) without consumer cost-sharing. However, Medicare beneficiaries face varying levels of cost-sharing for select ACIP-recommended vaccines. These differences in beneficiary cost-sharing are not grounded in clinical effectiveness. Recognizing the need to improve rates in vaccine uptake, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has encouraged Medicare Part D plans to offer more generous coverage for Part D-covered recommended immunizations.5,6 Yet high out-of-pocket costs persist for some evidence-based vaccinations.

This brief addresses the policy context of coverage and cost-sharing for vaccines in the Medicare program, the impact of beneficiary cost-sharing on vaccine uptake, and recommendations for policymakers to implement cost-sharing vaccine strategies to better protect the health of Medicare beneficiaries.

Coverage and Cost-Sharing for Vaccines in Medicare

Coverage and Cost-Sharing for Vaccines in Medicare

1965 through Medicare Modernization Act of 2003

As originally enacted in 1965, the Medicare program generally did not provide coverage[a] for drugs or vaccinations. An exception was made for outpatient coverage of physician-administered drugs in Medicare Part B, out of concern that without this exception, physicians might hospitalize patients in order to obtain coverage through Medicare Part A.7,8 The breadth of Part B coverage – for vaccines and other services – evolved considerably between 1965 and 2003. On the eve of passage of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA), Part B provided coverage – with consumer cost-sharing – of more than 450 drugs,7 including vaccinations for pneumococcal pneumonia, influenza, and hepatitis B (for individuals at high or intermediate risk of contracting hepatitis B).2 The features of Medicare Parts A, B, and D are reviewed in Table 1.

In general, fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with Part B coverage who have satisfied the Part B deductible are responsible for 20% of Medicare’s allowed amount for all Part B-covered physician-administered drugs[b].

Specific exceptions were made for the pneumococcal vaccination in 1981 and the influenza vaccination in 1993, which were (and remain) covered without beneficiary cost-sharing.9 (Figure 1)

Medicare Modernization Act

The enactment of the MMA in 2003 transferred responsibility for most Medicare prescription drug spending to subsidized Part D plans. In doing so, the MMA took care not to disturb existing coverage under Part B, including Part B-covered vaccinations. Section 101 of the MMA, codified at 42 USC 1395w-102, amended the Social Security Act to provide:

A drug prescribed for a part D eligible individual that would otherwise be a covered part D drug under this part shall not be so considered if payment for such drug as so prescribed and dispensed or administered with respect to that individual is available (or would be available but for the application of a deductible) under part A or B for that individual.

The implication of this provision is that vaccinations “directly related to the treatment of an injury or direct exposure to a disease or condition” remain the responsibility of Part B.10 Vaccinations that were covered by Part B at the time of the enactment of the MMA also remain Part B drugs. All other commercially available vaccinations that are medically necessary to prevent illness are generally covered through Medicare Part D.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

Section 1001 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) created a Section 2713 of the Public Health Service Act (“Coverage of Preventive Health Services”) requiring non-grandfathered commercial health plans to cover, without consumer cost-sharing, grade A or B services recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). The new Section 2713 also required non-grandfathered commercial health plans to cover all age-appropriate vaccinations recommended by the ACIP. Non-grandfathered health plans must cover these services and vaccinations subject to reasonable medical management techniques (e.g., requirements to use in-network providers).

Section 4104 of the ACA, “Removal of Barriers to Preventive Services in Medicare,” in some respects, provides similar protection against cost sharing for Medicare beneficiaries. The text of this section makes extensive cross-references to various portions of Medicare law as codified in the Social Security Act. In pertinent part, Section 4104 provides coverage for certain preventive services that were previously delineated in the Social Security Act with no beneficiary cost-share, so long as the services carry a USPSTF A or B recommendation. The ACA also provided a process by which the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services may update the Medicare benefits structure as to provide coverage without cost-sharing for new USPSTF recommended services (even if such services were not previously Medicare benefits). Unlike Section 1001, which eliminates consumer cost-sharing for ACIP recommended-vaccinations in non-Medicare health insurance plans, Section 4104 does not explicitly require zero-dollar cost-sharing for Medicare beneficiaries when receiving age-appropriate vaccinations recommended by the ACIP. However, Part B-covered vaccinations (i.e., pneumococcal, influenza, and hepatitis B for individuals at high- or medium-risk) were previously delineated as covered preventive services in the statue as described above. Of these, pneumococcal and influenza vaccines were already covered without cost-sharing. Thus, with the exception of the hepatitis B vaccine – which is now available to high- and medium-risk beneficiaries without cost-sharing – Section 4104 did not eliminate consumer cost-sharing for ACIP-recommended vaccines. (Table 2)

Therefore, despite the title of the section – “removal of barriers to preventive services in Medicare” – and the apparent parallels to Section 1001/2713, Section 4104 provided comparatively less protection from cost sharing for Medicare beneficiaries than those enrolled in non-Medicare health plans. The ultimate effect is that individuals over age 65 now generally receive less generous immunization benefits than benefits provided to individuals under age 65 – despite their high clinical benefit from these preventive care services. Since it is unlikely that Congress would have intended such an outcome, it appears that the intended spirit of the ACA’s cost-sharing protections for vaccine use was not achieved.

Implications for Access

Implications for Access

It is critical to emphasize that distinctions between Part B vaccination coverage and Part D vaccination coverage, and corresponding protections against cost-sharing, do not relate to clinical effectiveness. Rather, these distinctions are better understood as artifacts of statutory history and the complexity of Medicare law. The implications of differential cost-sharing strategies are noteworthy, and these impacts may be significant with respect to both patient-centered outcomes and total costs of care.

Differences in Medicare Cost-Sharing for ACIP Recommended Vaccines

A February 2016 report released by Avalere Health reported that all stand-alone Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Plans (PDPs) require cost-sharing for Part D-covered immunizations, as do most Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug Plans (MA-PDPs), accounting for 88% of MA-PDP enrollment.12 Although CMS suggested that reductions in cost-sharing for recommended vaccines are warranted in two recent Part D call letters,5,6 the amount of cost-sharing varies considerably by plan. On average, beneficiaries not receiving the low-income subsidy are typically subject to cost sharing of between $42 and $54 per Part D vaccination (for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug Plans) or $14 and $102 (for beneficiaries in stand-alone PDPs). Herpes zoster vaccination tends to have the highest cost sharing, with a typical copayment of more than $50.12 As detailed above, the three Part B-covered vaccinations are not subject to Part D cost-sharing.

Table 3 illustrates the differences in how ACIP-recommended vaccinations for adults are covered in non-grandfathered commercial health plans relative to Medicare beneficiaries with Part B and Part D coverage.

Literature on Impact of Consumer Cost-Sharing on Vaccine Use

Literature on Impact of Consumer Cost-Sharing on Vaccine Use

A rich body of literature clearly indicates that increasing consumer cost-sharing for high-value services tends to decrease the receipt of those services by Medicare beneficiaries, especially among poorer beneficiaries and those with multiple chronic clinical conditions.15 The literature is also clear that the ACA’s elimination of beneficiary cost-sharing for many preventive services has generally increased receipt of those services, with positive implications for socioeconomic disparities.16–22

While the published literature on immunizations and cost-related nonadherence is more limited, it is reasonable to assume that the impact of beneficiary cost-sharing on service receipt is little different than the impact of cost-sharing on receipt of preventive services more generally. Table 4 summarizes results from six studies on cost-sharing for immunizations.22–27 (Two reflect changes in vaccination receipt corresponding to both reductions in cost-sharing and increases in health insurance coverage.24,25)

Perceptions among clinicians confirm that increasing levels of consumer cost-sharing can interfere with receipt of Part D-covered vaccinations. According to 2010 surveys from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), 69% of pharmacies not stocking the herpes zoster immunization cited beneficiaries’ difficulty affording the cost-sharing for the vaccination as influencing their decision, as did 86% of physicians not stocking the vaccination.2 The GAO data suggest that these decisions not to stock – in part due to concerns about limited uptake given beneficiary cost-sharing – are common: only 31% of physician offices stock the herpes zoster vaccination, even as more than 90% of physician offices stock the pneumococcal vaccination. Pharmacies are similarly less likely to stock the zoster vaccination.

When administered in accordance with ACIP guidelines, the value of immunizations is high: the price of one quality-adjusted life year (QALY, a measure used in determining cost-effectiveness) obtained through vaccination is often far less the cost per QALY of many other common medical services and interventions. As shown in Table 5, researchers have found costs per QALY that are competitive with other recommended preventive services,28,29 and less than the commonly accepted threshold of $100,000 per QALY. Apart from cost effectiveness analysis, researchers have estimated that the 18 million vaccine-preventable cases of influenza, pneumococcal pneumonia, and herpes zoster each year lead to $5.8 billion in inpatient costs, $2.1 billion in outpatient costs, and $235 million in medication costs.1

Implications and Recommendations

Implications and Recommendations

Consumer cost-sharing for selected Part D-covered vaccinations contributes to sub-optimal vaccination rates for high-value ACIP-recommended immunizations that have been demonstrated to reduce morbidity and mortality. The tenants of value-based insurance design – which emphasize the need to align consumer cost-sharing with clinical benefit – would suggest that cost-sharing must be minimal for these vaccinations – especially for those patient populations who are likely to benefit the most from their use.

Accordingly, policymakers should seek opportunities to address differences in consumer cost-sharing that are artifacts of statutory history rather than reflections of differences in clinical importance. Implications of the available peer-reviewed literature clearly support the elimination of cost sharing for Medicare beneficiaries receiving immunizations recommended and used in accordance with the ACIP guidelines. To this end, policymakers should seek to ensure that the immunization coverage received by 65-year-old Americans is no less generous than the full coverage received by younger Americans.

Policy options to address cost-related barriers to receipt of immunizations among Medicare beneficiaries include:

- CMS should continue to encourage Part D plan sponsors to voluntarily cover vaccinations with $0 or minimal cost-sharing.[c],5,6 CMS might strengthen such encouragement by adjusting the plan finder algorithm as to favor PDPs that implement high-value benefit designs that vary cost-sharing on clinical importance rather than simply acquisition costs. Generous coverage for ACIP-recommended immunizations would be a hallmark of high-value benefit designs.

- At present, the stars system for Medicare Prescription Drug plans includes a measure of influenza vaccination receipt. Receipt of pneumococcal vaccination is reported as a “display-only” measure, but not included in the stars measures. In consultation with key stakeholders, CMS should consider including receipt of both Part B and Part D-covered ACIP-recommended immunizations in the Stars formula under the “Staying Healthy” stars domain.33

- At present, the stars system for Medicare Prescription Drug plans includes measures related to member experience and customer service, as well as several measures related to chronic disease medication adherence and medication safety. There are no stars measures pertaining to receipt of receipt of Part D-covered ACIP-recommended immunizations. Since Part D-only plans lack the total-cost-of-care accountability of Medicare Advantage plans – accountability that appears to encourage more generous coverage of evidence-based, utilization-averting immunizations12 – prevention-oriented quality measures are especially critical in this context. In consultation with key stakeholders, CMS should remedy the highly problematic lack of appropriate incentives through updates to the Part D star system.33

Conclusion

Conclusion

More than 3.7 million cases per year of vaccine-preventable illnesses occur among American adults age 65 and older.1 Influenza, pneumococcal, and herpes zoster vaccination account for the vast share of these cases, but only the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are routinely available without cost-share to Medicare beneficiaries. As new immunizations become available under Part D, current policy that permits plans to impose substantial consumer cost-sharing will hinder uptake of new and existing high-value Part D vaccinations alike. Changes in federal policy to better align cost-sharing levels with the clinical value to the patient or to society at large can ensure that MA-PDs and PDPs have the right incentives to keep their members healthy, reduce the incidence of preventable disease, and avert downstream health care costs.

[a] Unless otherwise indicated, the term “coverage” does not necessarily indicate first-dollar coverage, i.e., coverage may be offered with or without beneficiary cost-sharing. [b] Many patients may not pay cost-sharing in this form or this amount, however, given enrollment in Medicaid, Medicare Advantage, or supplemental coverage.

[c] The language reads as follows:

Despite ACIP recommendations and Healthy People 2020 targets, adult immunization rates still remain low. We encourage Part D sponsors to consider offering $0 or low cost-sharing for vaccines to promote this important benefit. While the inclusion of a dedicated vaccine tier or a Select Care/Select Diabetes tier that contains vaccine products as part of a 5 or 6 tier formulary structure is not a requirement, sponsors who choose to offer one of these formulary tiers must set the cost-sharing at $0 for that tier.

References

- Ozawa S, Portnoy A, Getaneh H, Clark S, Knoll M, Bishai D, Yang HK, Patwardhan PD. Modeling The Economic Burden Of Adult Vaccine-Preventable Diseases In The United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2124-2132. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0462.

- Government Accountability Office. Medicare: Many Factors, Including Administrative Challenges, Affect Access to Part D Vaccinations. 2011;(GAO-12-61). http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-61. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Williams WW, Lu P-J, O’Halloran A, Kim DK, Grohskopf LA, Pilishvili T, Skoff TH, Nelson NP, Harpaz R, Markowitz LE, Rodriguez-Lainz A, Bridges CB. Surveillance of Vaccination Coverage Among Adult Populations — United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(1):1-36. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6501a1.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotin. Immunization and Infectious Diseases | Healthy People 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) 2016 Medicare Advantage Capitation Rates and Medicare Advantage and Part D Payment Policies and Final Call Letter.; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2016.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) 2017 Medicare Advantage Capitation Rates and Medicare Advantage and Part D Payment Policies and Final Call Letter.; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2017.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Oliver TR, Lee PR, Lipton HL. A Political History of Medicare and Prescription Drug Coverage. Milbank Q. 2004;82(2):283-354. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00311.x.

- Megellas MM. Medicare Modernization: The New Prescription Drug Benefit and Redesigned Part B and Part C. Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2006;19(1):21-23.

- Goodwin SM, Anderson GF. Effect of Cost-Sharing Reductions on Preventive Service Use Among Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2(1). doi:10.5600/mmrr.002.01.a03.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Vaccine and Vaccine Administration Payments Under Medicare Part D.; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Vaccines-Part-D-Factsheet-ICN908764.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight. Affordable Care Act Implementation FAQs – Set 12. CMS; 2013. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/aca_implementation_faqs12.html. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Avalere Health. Adult Vaccine Coverage in Medicare Part D Plans.; 2016. http://go.avalere.com/acton/attachment/12909/f-0297/1/-/-/-/-/20160217_Medicare%20Vaccines%20Coverage%20Paper.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2017.

- Kim DK, Riley LE, Harriman KH, Hunter P, Bridges CB, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older, United States, 2017. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(3):209. doi:10.7326/M16-2936.

- Humana Medicare – Walmart Prescription Drug Plan. . Accessed February 24, 2017.

- Fendrick AM, Oesterle SL, Lee HM, Padaley P, Eagle T, Chernew M, Mueller PP, Adams J, Agostini JV, Montagano C. Incorporating Value-Based Insurance Design to Improve Chronic Disease Management in the Medicare Advantage Program. Weat Health Policy Center and University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design; 2016. http://vbidcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/MA-White-Paper_final-8-16-16.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2017.

- Jena AB, Huang J, Fireman B, Fung V, Gazelle S, Landrum MB, Chernew M, Newhouse JP, Hsu J. Screening Mammography for Free: Impact of Eliminating Cost Sharing on Cancer Screening Rates. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(1):191-206. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12486.

- Sabatino SA, Thompson TD, Guy GP, de Moor JS, Tangka FK. Mammography Use Among Medicare Beneficiaries After Elimination of Cost Sharing. Med Care. 2016;54(4):394-399. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000495.

- Cooper GS, Kou TD, Schluchter MD, Dor A, Koroukian SM. Changes in Receipt of Cancer Screening in Medicare Beneficiaries Following the Affordable Care Act. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5). doi:10.1093/jnci/djv374.

- Hamman MK, Kapinos KA. Affordable Care Act Provision Lowered Out-Of-Pocket Cost And Increased Colonoscopy Rates Among Men In Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(12):2069-2076. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0571.

- Richman I, Asch SM, Bhattacharya J, Owens DK. Colorectal Cancer Screening in the Era of the Affordable Care Act. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):315-320. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3504-2.

- Fedewa SA, Goodman M, Flanders WD, Han X, Smith RA, M. Ward E, Doubeni CA, Sauer AG, Jemal A. Elimination of cost-sharing and receipt of screening for colorectal and breast cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(18):3272-3280. doi:10.1002/cncr.29494.

- Han X, Robin Yabroff K, Guy Jr. GP, Zheng Z, Jemal A. Has Recommended Preventive Service Use Increased After Elimination of Cost-Sharing as Part of the Affordable Care Act in the United States? Prev Med. 2015;78:85-91. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.012.

- Jensen GA, Salloum RG, Hu J, Ferdows NB, Tarraf W. A Slow Start: Use of Preventive Services Among Seniors Following the Affordable Care Act’s Enhancement of Medicare Benefits in the U.S. Prev Med. 2015;76:37-42. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.023.

- Lipton BJ, Decker SL. ACA Provisions Associated With Increase In Percentage Of Young Adult Women Initiating And Completing The HPV Vaccine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(5):757-764. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1302.

- Lau JS, Adams SH, Park MJ, Boscardin WJ, Irwin CE. Improvement in Preventive Care of Young Adults After the Affordable Care Act: The Affordable Care Act Is Helping. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(12):1101. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1691.

- Nexøe J, Kragstrup J, Rønne T. Impact of Postal Invitations and User Fee on Influenza Vaccination Rates Among the Elderly. a Randomized Controlled Trial in General Practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1997;15(2):109-112.

- Satterthwaite P. A Randomised Intervention Study to Examine the Effect on Immunisation Coverage of Making Influenza Vaccine Available at No Cost. N Z Med J. 1997;110(1038):58-60.

- Black WC, Gareen IF, Soneji SS, Sicks JD, Keeler EB, Aberle DR, Naeim A, Church TR, Silvestri GA, Gorelick J, Gatsonis C. Cost-Effectiveness of CT Screening in the National Lung Screening Trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1793-1802. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312547.

- Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Brenner H. Cost-Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33(1):88-100. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxr004.

- Maciosek MV, Solberg LI, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Goodman MJ. Influenza Vaccination Health Impact and Cost Effectiveness Among Adults Aged 50 to 64 and 65 and Older. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):72-79. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.008.

- Chen J, O’Brien MA, Yang HK, Grabenstein JD, Dasbach EJ. Cost-Effectiveness of Pneumococcal Vaccines for Adults in the United States. Adv Ther. 2014;31(4):392-409. doi:10.1007/s12325-014-0115-y.

- Le P, Rothberg MB. Determining the Optimal Vaccination Schedule for Herpes Zoster: a Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):159-167. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3844-6.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Part C and D Performance Data. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/PerformanceData.html. Published February 2, 2017. Accessed February 25, 2017.