Enhancing Flexibility in HSA-HDHP Design by Applying V-BID & Clinical Nuance Principles to Better Align the “Preventive Services Safe Harbor”

Enhancing Flexibility in HSA-HDHP Design by Applying V-BID & Clinical Nuance Principles to Better Align the “Preventive Services Safe Harbor”

Introduction

Shifting the health care system from “volume-to-value” has become a common theme in health care reform discussions. Benefit designs that engage consumers in their health care, while also encouraging access to high-value and appropriate care, are of particular interest.

Value-based insurance design (V-BID) seeks to achieve this by connecting benefit design with high-value care. V-BID refers to health insurance benefit design and payment models that attempt to engage consumers by encouraging them to become more active in their health care choices by providing flexibility to align out-of-pocket costs, such as deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance, with the value of services. In this way, V-BID furthers consumer access to high-value clinical services while recognizing the importance of maintaining and promoting affordability.

Regulatory Challenges with Incorporating V-BID into High Deductible Health Plans

A broad range of stakeholders spanning employers, payers, providers, consumer and patient groups, as well as academic centers have expressed interest in addressing regulatory challenges with incorporating the principles of V-BID and the related concept of “clinical nuance” into the context of high deductible health plans (HDHPs) by re-aligning what is known as the “preventive care safe harbor.” As discussed below in more detail, current regulatory guidance generally excludes services from the safe harbor if they are meant to treat “an existing illness, injury, or condition.”

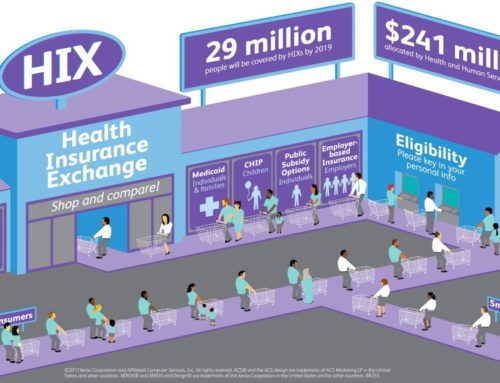

An HDHP, as defined in the Internal Revenue Code (“Code”), is a health plan that satisfies certain requirements regarding minimum deductibles and maximum out-of-pocket expenses.1 HDHPs can be paired with Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) that allow consumers and employers to save pre-tax dollars to pay for eligible health care services and can be carried over year-to-year.2 (We refer to these HSA-eligible plans as HSA-HDHPs). HSA-HDHPs have grown dramatically in popularity,3 as they provide for affordable coverage and as noted are designed to engage consumers in their health care.

HSA-HDHPs are required to have defined minimum deductibles, and in general, are not allowed to provide benefits for any year until the deductible for that year is satisfied.4 While the “preventive care safe harbor” provides some exceptions to this rule, the limitations of this safe harbor combined with the minimum deductible requirements may limit the ability of HDHPs to offer many evidence-based, high value services on a predeductible basis. Consequently, for regulatory reasons, services that are recommended to help effectively manage an existing chronic condition often cannot be covered in an HSA-HDHP until the deductible has been met. For example, HDHPs may be prevented from providing benefits for certain evidence-based disease management services such as insulin, eye and foot exams, and glucose monitoring supplies for patients with diabetes prior to the deductible being met. There is growing public interest in addressing this concern by incorporating the principles of VBID into the context of an HSA-HDHP.

The specific challenge with offering these high value services pre-deductible in an HSA-HDHP comes from a current interpretation of the scope of the preventive care safe harbor under the Code. The Code provides a safe harbor that allows plans to voluntarily cover some preventive services prior to a deductible being met. The Code states that “[a] plan shall not fail to be treated as a high deductible health plan for reason of failing to have a deductible for preventive care . . . .”5

The concern is that the regulatory definition of preventive services may exclude many high-value services that could otherwise be encouraged through VBID.6 Currently, the guidance regarding the safe harbor excludes services or benefits meant to treat “an existing illness, injury or condition.”7 Taken literally, this can be read to suggest that management of a chronic condition is not “preventive” within the meaning of the safe harbor because management of the condition might be said to reflect treatment of an existing illness. In turn, this limits the flexibility for HDHPs to encourage the cost-effective use of high-value services related to many chronic conditions. This raises an important policy issue given that chronic conditions are estimated to account for close to 86 percent of total U.S. health spending.8

Recent Accomplishments: Executive Order 13877 and Chronic Disease Management Act of 2021

On June 24, 2019, President Trump signed an Executive Order (EO) 13877 on improving price and quality transparency in American healthcare. Section 6 of the EO titled, “Empowering Patients by Enhancing Control Over Their Healthcare Resources” states that the Secretary of the Treasury will issue guidance, “to expand the ability of patients to select high-deductible health plans that can be used alongside an HSA, and that cover low-cost preventive care, before the deductible, for medical care that helps maintain health status for individuals with chronic conditions.” 9

On July 17, 2019, following the EO, the U.S. Department of Treasury released Notice 2019-45, expanding the coverage of HAS-HDHP plans for specified medications and services for chronic diseases prior to meeting the plan deductible.

On April 28, 2021, Senators John Thune (R-S.D.) and Tom Caper (D-DE) re-introduced the Chronic Disease Management Act (CDMA) in the United States Senate (S. 1424). This bill builds upon previous versions (S. 3200 and S. 1948) and follows guidance issued by the US Department of Treasury in 2019 to further increase the flexibility of HSA-HDHPs to cover chronic disease services on pre-deductible basis.

Both Section 6 of the EO 13877 and the CDMA of 2021 have broad bipartisan support and have the potential to expand needed coverage to millions of Americans. In addition, this legislation aims to decrease healthcare spending by helping patients to successfully manage their chronic conditions, reducing the need for costly, downstream health interventions.

These actions are the result of over a decade of advocacy by the University of Michigan V-BID Center and its many collaborators.

Broad Stakeholder Coalition Effort

A range of stakeholders – including employers, providers, health plans, health and life sciences companies, consumer and patient groups, think tanks, and academic centers – are supportive of and interested in addressing these issues in order to provide those creating HSA-HDHPs greater flexibility to adopt innovative benefit designs that improve consumers access to care while still providing for affordability, taking into account both premiums and cost sharing. Interest has also been raised among regulators in further exploring the issue as well as on Capitol Hill to possibly create a solution through legislation.

Additionally, this collaboration can potentially serve as a constructive platform to promote the tenets of VBID more generally and to encourage their adoption in other contexts, such as in Medicare Advantage (where the Administration and Congress have both expressed interest), and to emphasize its clear synergies with value-based payment reform initiatives. More broadly, it is also an important opportunity to encourage the integration of health reform approaches that focus on harnessing the power of the consumer experience through coverage and benefit design with reforms focused on improving quality of care and efficiency through delivery system transformation.

To learn more about this effort, please contact the coalition at smarterhc.org, or by emailing info@smarterhc.org.

References:

1. 26 U.S.C. §223(c)(2). Accessed at: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-13-57.pdf.

2. Other plans with high deductibles that don’t meet the specific requirements can also be offered, provided that they meet other regulatory requirements, such as those that might apply under the Affordable Care Act – but these would not qualify as HDHPs under the Code and consumers could not couple these with an HSA.

3. See https://ahip.org/new-census-survey-shows-continued-growth-in-hsa-enrollment/.

4. See IRS Notice 2004-23.

5. 26 USC Section 223(c)(2)(C). Accessed at: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-13-57.pdf.

6. Michael Chernew, J. Sanford Schwartz, and Mark Fendrick, “Reconciling Prevention And Value In The Health Care System,” Health Affairs Blog, March 11, 2015. Accessed at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/03/11/reconciling-prevention-and-value-in-the-health-care-system/.

7. IRS Notice 2004-23. Accessed at: https://www.irs.gov/irb/2004-15_IRB/ar10.html. See also IRS Notice 2013-57, where the IRS additionally clarifies that preventive services required to be covered without cost sharing under the ACA are also treated as preventive services under this safe harbor. Accessed at: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-13-57.pdf.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed at: http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/.

9. “Improving Price and Quality Transparency in American Healthcare To Put Patients First.” Federal Register, June 27, 2019. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/06/27/2019-13945/improving-price-and-quality-transparency-in-american-healthcare-to-put-patients-first.