Originally Produced: February 2013 Updated: July 2016.

V-BID in Action: Driving Value through Clinically Nuanced Incentives

Introduction

Value-Based Insurance Design (V-BID) is an innovative approach that can improve clinical outcomes and contain costs. The basic premise of V-BID is to align consumer incentives with value – by reducing barriers to high-value health services and providers (“carrots“) and discouraging the use of low-value health services and providers (“sticks”). When “carrots” are coupled with “sticks” in a clinically nuanced manner, V-BID improves health care quality and controls spending growth.i

Dangers of a Blunt Approach

It has been shown that when patients are faced with increases in cost-sharing applied to all services regardless of clinical benefit, they reduce their use of both high-value and low-value services. While this blunt approach potentially lowers expenditures in the short-term, the cost-related noncompliance with high- value services leads to inferior health outcomes and higher overall costs in certain clinical circumstances.ii,iii,iv

Conversely, decreases in cost-sharing applied to all services regardless of clinical benefit can lead to overuse or misuse of services that are potentially harmful or provide little clinical value.v This is also inefficient and costly. To efficiently reallocate medical spending and optimize population health, the basic tenets of clinical nuance must be considered. These tenets recognize that:

1) medical services differ in the benefit provided; and 2) the clinical benefit derived from a specific service depends on the patient using it.

Incentive-Based V-BID Improves Quality

Incentive-based V-BID programs reduce cost-sharing for services that have strong evidence of high clinical value—typically primary preventive services and treatments for chronic diseases. Multiple peer-reviewed studies demonstrate improved clinical outcomes in V-BID incentive programs.

From the payer’s perspective, the cost of incentive-only “carrot” based V-BID programs depends on whether the added spending on high-value services is offset by a decrease in adverse events, such as hospitalizations. While these high-value services are cost-effective and improve quality, many are not cost-saving. Four studies assessing V-BID’s impact on resource use and cost concluded that the added costs attributable to the modest increases in targeted high-value services did not raise aggregate direct medical costs over the medium term, but few reported net savings. However, research suggests that non-medical economic effects—such as the improvement in productivity associated with better health—can substantially impact the financial results of V-BID programs.vi,vii

While significant cost-savings are unlikely with incentive-only “carrot” programs, a V-BID program that combines reductions in cost-sharing for high-value services and increases in cost-sharing for low-value services can both improve quality and achieve net cost savings.

Adding Disincentives Achieves Net Cost Savings and Quality Evidence suggests significant opportunities exist to save money without sacrificing high-quality care. For example, in 2011, the lowest available estimates of waste in the US health care system exceeded 20% of total health care expenditures, with a significant amount due to overuse.viii Judiciously combining the “carrot” and “stick” approach, V-BID programs can tap into these potential savings while ensuring quality. When adding disincentives to V-BID, two approaches exist:

- Increase cost-sharing on services not considered high-value

- Identify low-value services for cost-sharing increases

While there are few studies about using V-BID to discourage low-value services, early evidence from two programs reveals increased cost-sharing is effective at reducing their use. In the first program, Mayo Clinic employees faced increased cost-sharing for specialty care visits ($25 co-payment for high-premium option) and other services including imaging, testing, and outpatient procedures (adding 10-20% co-insurance, depending on the option). For high-value services, such as preventive services and visits to primary care providers, all cost-sharing was removed. Decreased use of specialist office visits (0.7 fewer visits per person for high-premium plans) and significantly decreased use of diagnostic testing, imaging, and outpatient procedures (across low- and high-premium plans) were found. These utilization patterns have been sustained for four years, with the exception of imaging which increased after year one of the program but still remains below expected utilization patterns.ix

In the second program, health care services were divided into tiers for public employees in Oregon. Cost-sharing was eliminated for certain high-value services, such as weight management and tobacco cessation. For other high-value services, such as office visits for chronic disease, cost-sharing was reduced. However, cost-sharing was increased for over-used or preference-sensitive services of low-value (some exceptions applied).x Between 2009/2010 and 2012, decreases of 15-17% occurred for targeted low-value procedures.xi

Identifying Low-Value Services

Low-value services result in either harm or no net benefit, such as services labeled with a D rating by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.xii Identifying low-value services can be challenging, since detailed clinical information is often required. Many services that are identified as high quality in certain clinical scenarios are considered low-value when used in other patient populations, clinical diagnoses or delivery settings. For example, cardiac catheterization, imaging for back pain, and colonoscopy can all be classified as high- or low-value depending on who receives them as well as when and where.

A Growing Movement to Discourage Low-Value Services Fortunately, there is a growing movement to both identify and discourage the use of low-value services. The ABIM Foundation, in association with Consumers Union, has launched Choosing Wisely, an initiative where medical specialty societies identify commonly used tests or procedures whose necessity should be questioned and discussed.xiii Thus far, twenty-six medical specialties have identified at least five low-value services within their respective fields while twelve additional societies are also preparing low-value services lists.

Substantial cost savings are available from efforts such as Choosing Wisely. Savings of more than $5 billion were estimated if the recommendations of a recent top five overused clinical services list across three primary care specialties were implemented in practice.xiv

Extending Low-Value Services to Low-Value Providers

In addition to utilizing the growing list of low-value services for disincentive V-BID programs, low-value providers can also be identified and avoided to both improve quality and control costs. A recent report from the Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System estimated that $189 billion in savings to Medicare would result if we were to “develop a value-based design that encourages beneficiaries to obtain care from high-performing care systems.”xv Reference pricing and centers of excellence are additional examples of tools to align financial incentives with value at the provider level.xvi Tiered or narrow network designations based on quality and not solely on price are additional strategies that are gaining momentum nationwide.

V-BID is Politically Nuanced

Even with these developments, attempts to address rising costs by decreasing utilization requires political nuance. V-BID is a politically palatable method to decrease utilization, because it focuses on reducing the use of low-value services and discouraging access to poorly performing providers. Health economists across the philosophical spectrum accept pricing mechanisms as legitimate means to persuade decreased utilization through free choice. xvii Additionally, consumers are familiar with the idea of cost-sharing as many health plans already vary the out-of-pocket cost for prescription drugs, although patients’ out-of-pocket costs are usually determined by acquisition price. Variations in cost-sharing based on clinical benefit achieved can be applied to previously studied health services and updated as research results become available. Moreover, qualitative research from focus groups suggests consumers may be willing to accept disincentives, provided the identification of low-value services is perceived as fair and transparent. xviii

Conclusion

The ultimate test of health reform will be whether it expands coverage in a way that promotes access to care, enhances personal accountability, improves health, and addresses rapidly rising costs. Although there is urgency to bend the health care cost curve, cost containment efforts should not produce avoidable reductions in quality of care. Key stakeholders—including a large and growing number of medical professional clinical societies—agree that discouraging low-value services must be part of the strategy. V-BID “sticks” can drive changes in utilization of low-value care, and when combined with “carrots” for high-value services, the result can simultaneously improve quality and contain costs. As evidence-driven approaches to identify high- and low-value services are coupled with carefully designed strategies for consumer education and communication, V-BID programs will only continue to grow in acceptance and use.

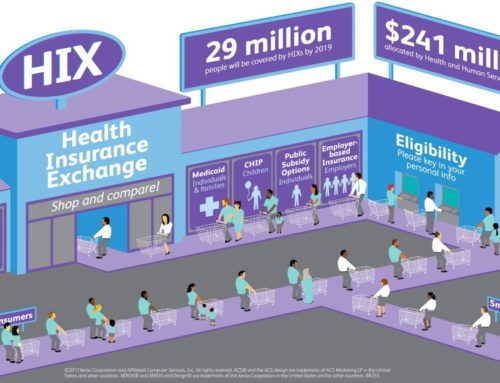

Clinical Nuance Infographic

References

i. University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. V-BID Center Brief. The Evidence for V-BID: Validating an Intuitive Concept. November 2012. Available at: http://vbidcenter.org/the-evidence-for-v-bid-validating-an-intuitive-concept/

ii. Goldman D, Joyce G, Zheng Y. Prescription Drug Cost Sharing: Associations With Medication And Medical Utilization And Spending And Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(1):61–9.

iii. Trivedi AN, Rakowski W, Ayanian JZ. Effect of Cost Sharing On Screening Mammography In Medicare Health Plans. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(4):375–83.

iv. Trivedi AN, Moloo H, Mor V. Increased Ambulatory Care Copayments And Hospitalizations Among The Elderly. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(4):320-28

v. Fendrick AM, Smith DG, Chernew ME. Applying Value-Based Insurance Design To Low-Value Health Services. Health Affairs. 2010;29(11):2017-21.

vi. Fendrick AM, Jinnett K, Parry T. Synergies At Work: Realizing The Full Value Of Health Investments. Integrated Benefits Institute, University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design, National Pharmaceutical Council; 2011.

vii. Nicholson S, Pauly MV, Polsky D, Sharda C, Szrek H, Berger ML. Measuring The Effects Of Work Loss On Productivity With Team Production. Health Economics. 2006;15(2):111–23

viii. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating Waste in US Health Care. JAMA. 2012; 307(14):1513-1516.

ix. Shah ND, Naessens JM, Wood DL, Stroebel RJ, Litchy W, Wagie A, et al. Mayo Clinic Employees Responded To New Requirements For Cost Sharing By Reducing Possibly Unneeded Health Services Use. Health Affairs. 2011;30(11):2134–41

x. Kapowich JM. Oregon’s Test Of Value-Based Insurance Design In Coverage For State Workers. Health Affairs. 2010; 29(11):2028–32.

xi. Personal communication with JM Kapowich (Oregon Public Employees’ and Oregon Educators Benefit Boards), 27 Nov 2012.

xii. US Preventive Services Task Force Ratings. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestask force.org/uspstf07/ratingsv2.htm

xiii. Choosing Wisely. An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Accessed at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/about-us/

xiv. Kale MS, Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. “Top 5” Lists Top $5 Billion. Arch Intern Med. 12/14/2011. Vol 171. (no 20); 1856-57.

xv. Confronting Costs: Stabilizing U.S. Health Spending While Moving Toward a High Performance Health Care System. The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System. January 2013. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Fund%20Report/2013/Jan/1653_Commission_confronting_costs_web_FINAL.pdf

xvi. Robinson JC, MacPherson K. Payers Test Reference Pricing and Centers of Excellence to Steer Patients to Low-Price and High-Quality Providers. Health Affairs, 31, no. 9 (2012):2028-2036.

xvii. Feldstein M. Obama’s plan isn’t the answer. Washington Post. July 27, 2009.

xviii. University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design. V-BID Center Brief. Probing the Public’s View on V-BID. June 2012.